1. Hurling Things that Hurt

Long before they had bullets, people used other projectiles to kill game and adversaries. Rocks predated spears, boomerangs, arrows, darts, and bolts. All had limited range, because they depended directly on the power of the human arm.

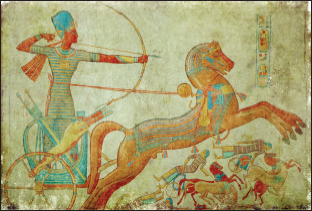

By some accounts, the bow dates back 15,000 years, to early Oranian and Caspian cultures. It enabled the Persians to conquer the civilized world. Around 5,000 B.C., Egypt managed to free itself from Persian domination, at least in part because the Egyptians became skilled in the use of bows and arrows.

By 1,000 B.C. Persian archers had adapted the bow for use by horsemen. Short recurve bows, suitable for use while on horseback, arrived as early as 480 B.C. The Turks are credited with launching arrows half a mile in flight in contests with sinew–backed recurves.

Evidently it was the Greeks who first studied ballistics, around 300 B.C. Their inspiration was no doubt the development of better armament. At that time, little was known about gravity and air resistance, the two main forces impeding a projectile in flight. Later, such bright lights as Isaac Newton, Leonardo da Vinci, Galileo, Francis Bacon, and Leonard Euler would examine how these forces could be measured and countered.

A hunter and his tracker scout for game atop a termite mound. Hunting is more than shooting.

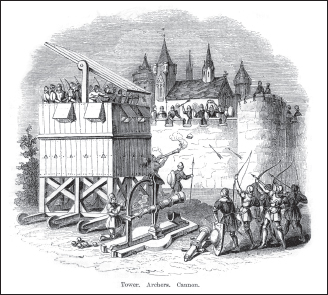

Early on, arrows helped people understand the principles of ballistics. The arrow’s arc was visible, and during the Middle Ages its role in battle can hardly be overstated. Years after gunpowder was invented, archers determined who would be the victor and the vanquished. At the Battle of Hastings in 1066, Normans drew their English foes onto the field with a false retreat, then drove arrows en masse toward the oncoming troops, inflicting heavy casualties to win the day. Unlike the Turks, English archers preferred a one–piece bow. It was called a longbow not for its tip-to-tip measure, but for the manner of the archer’s draw, with an anchor point at the ear or cheek. Short bows of the day were commonly drawn to the chest. The English adopted the Viking and Norman tactic of hailing arrows into distant troops. But they could be deadly up close, too. A charge toward well–positioned archers resulted in huge casualties, even when the attackers had armor. The armor wearied the advancing foot soldiers who wore it. English bowmen aimed for the joints in the armor and for the exposed head and neck of any man so foolish as to shed his helmet on a hot day. They shot deliberately at horses during a cavalry assault, not only to cripple and kill but to make the steeds unmanageable and spill their riders.

By becoming proficient in the use of bows and arrows, ancient Egyptians were able to free themselves from Persian domination.

Longbows usually spelled the difference between victory or defeat during the middle ages.

Modern arrows are colorful and accurate, uniform in weight and spine. But primitive shafts from longbows and recurves shaped history!

In those days, English conscripts were required to practice with their bows. Royal statutes dictated that anyone earning less than 100 pence a year had to own a bow and arrows—which could at any time be inspected! Poachers in Sherwood Forest (hung with their own bowstrings if caught in the act) were offered a pardon if they agreed to serve the king as archers. Many did, and a contingent of these outlaws won a spectacular victory at Halidon Hill in 1333. Their arrows killed 4,000 Scots in a conflict that left only 14 English dead. At Crecy (1346) and Agincourt (1415), England’s archers vanquished the French army with volleys of arrows.

The English longbow became an everyday tool. Specimens were not embellished or displayed as were early firearms or swords. Bow wood deteriorated with age and weather. Only a few examples remain: unfinished staves in the Tower of London and a bow recovered in 1841 from the wreck of the Mary Rose, sunk in 1545. The “war” bow of English legend averaged six feet in length with a flat back and curved belly. Yew was the preferred wood, but English yew couldn’t match that from Mediterranean countries for purity and straightness. Some of the best bows derived from Spanish wood. After the longbow gained its fearsome reputation, Spain forbade the growing of yew on the premise that it might find its way to England and thence to battlefields in which Spain might feel its sting. Desperate for staves, the English got around the ban by requiring that some staves be included with every shipment of Mediterranean wine!

An early version of the crossbow, a popular weapon during the 15th century.

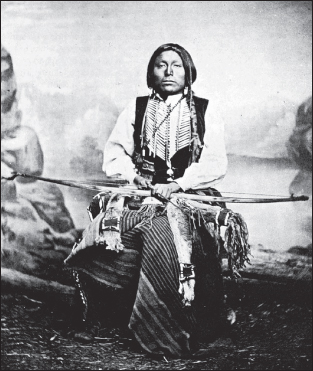

According to Samuel Colt, Indians could “shoot their bows faster than you can fire a revolver.”

In North America, bows varied regionally in shape and construction. Generally, those with wide, flat limbs were fashioned from soft woods like the yew preferred by Indians in the Pacific Northwest. Ash, hickory, and other hardwoods in the East, and Osage orange in the Midwest, provided the raw material for slender bows, rectangular in cross-section. Some tribes added sinew to protect the back of the bow at its extreme arch. Strips of horn occasionally found their way onto the bellies of bows. Unlike sinew, horn has no virtually no stretch; but it delivers resilience under compression.

Before horses became available on the plains, bows of Indians there averaged nearly five feet from tip to tip, almost as long as bows used by forest tribes east of the Mississippi. Mounted warriors soon switched to bows around 40 inches long, like those favored by Northwest tribes. Arrows favored by Eastern Indians were long and beautifully made, with short feathers to clear the bow handle while the hunter was stalking. Accuracy was of paramount importance because one shot was all that could be expected. On the plains, where hunters rode alongside bison and elk and shot several arrows quickly at short range, accuracy mattered less. And arrows driven through bison seldom survived for a second use. Fletching was long because the crude shafts needed strong steering and because the feathers spend little time against the bow handle before the shot. Raised nocks aided the “pinch” grip preferred by horsemen under pressure to shoot quickly. Most big game arrowheads were small, to penetrate, while arrows for smaller animals had bigger heads.

The Plains Indian pushed the bow as much as he pulled the string. This technique enabled him to shoot quickly and get lots of thrust from a short but strong bow. He normally drew only to the chest, and well shy of the arrowhead—a 24 inch arrow might be pulled 20 inches. That draw stacked enough thrust to drive arrows through big animals. Indians did not soon abandon their bows for muskets. In fact, the speed with which repeat arrows could be launched kept the bow popular among mounted warriors until Samuel Colt’s Walker revolver came along in 1839. “Bigfoot” Walker, the nineteenth century Texas Ranger who helped Colt develop that 4–lb handgun, respected the plains Indian and his bow. “I have seen a great many men in my time spitted with ‘dogwood switches’ … [Indians] can shoot their arrows faster than you can fire a revolver, and almost with the accuracy of a rifle at the distance of fifty or sixty yards.”

Even in the East, the first flintlock muskets had little to offer red men skilled with the bow. These guns were not only slow to load; they were unwieldy and delivered poor accuracy—besides making a frightful noise and spewing thick smoke that obscured the animal or adversary. Powder and ball had to be bought or stolen, but arrows could be fashioned in the field.

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- CONTENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- SECTION I: BALLISTICS IN HISTORY

- SECTION II: THE MUSCLE BEHIND THE SHOT

- SECTION III: BULLETS—THE INSIDE STORY

- SECTION IV: SPEED, ENERGY, AND ARC

- SECTION V : PUTTING BALLISTICS TO WORK

- SECTION VI: FOR LONGER REACH

- BALLISTICS TABLES FOR MODERN SPORTING RIFLES

- GLOSSARY