10. DuPont: Powder Pioneer

After its inception in 1802 on Delaware’s Brandywine River, E. I. DuPont de Nemours had grown with the country. By the end of World War II, any list of major US corporations included the chemical giant. But the varied product line it fielded then could hardly have been imagined by its founder, French immigrant Eleuthere Irenee DuPont.

Not that DuPont lacked confidence in his products. “I can make better black powder than what your country has in its magazines,” DuPont told Alexander Hamilton. Apparently the claim impressed our young government. Soon the enterprising DuPont built a plant in Wilmington. The new propellant satisfied US ordnance officers. Gunpowder remained the firm’s primary product for most of the nineteenth century. In the 1880s DuPont added a plant at Carney’s Point to boost capacity. During World War I, 25,000 people went to work at this Brandywine facility, providing more than 80 percent of the powders used by the Allies (the British and French, the Danes and Russians, as well as US troops)!

The 1930s humbled many mighty corporations. DuPont weathered not only the Depression, but scathing political attacks from some US senators who accused the company of war-mongering. As Hitler revved up his war machine and the US prepared to rearm, DuPont boosted its production capacity. But the company was fed up with the treatment it had received from Congress. Larry Werner, who worked many years as a DuPont engineer, recalled that “Rather than build new plants, the company contracted to operate government facilities for $1 a year. That way, it could not be said to have had a stake in the hostilities. Of course, the US government had no powder works that could match DuPont’s, so the firm supervised construction of seven factories modeled on its Carney’s Point plant. Another went up in Canada. At the height of the second world war, these operations shipped a million pounds of powder a day. We fielded 16 million guys in uniform then, and they used a lot of ammo!”

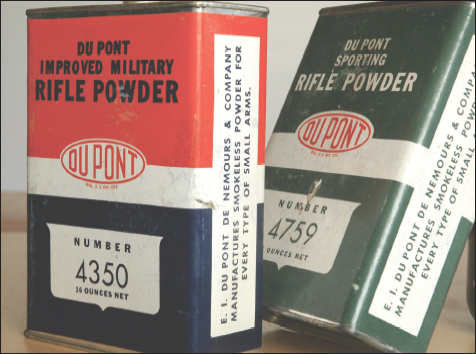

DuPont’s IMR (Improved Military Rifle) moniker dates way back. These early metal cans have been replaced by plastic.

After an armistice, the government took control of the propellant plants. Carney’s Point stayed in production for DuPont. So did the Belin Works at Scranton, Penn. “Belin made black powder for the government,” says Larry. It was used as an igniter in artillery shells. A plant explosion in 1971 sent debris over the nearby interstate and littered runways at the local airport. The plant closed right away but was reopened for military production to supply troops in Vietnam. “In 1973 Marv Gearhardt and Harold Owens bought the Belin Works for $400,000 and contracted to make powder,” continued Larry. “Their company, GOEX, later moved to Louisiana, and the Scranton facility shut down.”

For best accuracy with wildcats, the die set must match the chamber. Tight tolerances rule!

Explosions at powder plants occur infrequently but can be serious. In June, 1969, an accident in the finishing area at Carney’s Point leveled it. A new finishing area was built at DuPont’s Potomac River Plant near Falling Waters, Va. In April, 1978, fire swept through the main mix house at Carney’s Point, shutting it down. That summer, DuPont contracted with Valleyfield Chemical Products in Quebec to produce commercial smokeless propellants. The Valleyfield plant was a Canadian factory built during World War II and operated by CIL, or Canadian Industries, Limited, a branch of the government. In 1982 Valleyfield Chemical was bought by Welland Chemical, which became EXPRO.

In December, 1986 DuPont sold its smokeless powder business to EXPRO. The IMR Powder Company established itself as a testing and marketing firm for EXPRO. IMR’s laboratory and offices in Plattsburg, New York, were kept to develop ballistics data for IMR powders and package and distribute them to dealers. EXPRO, with an annual manufacturing capacity of more than 10 million pounds, also produces powders for Alliant and other brands. Though DuPont owned 70 percent of Remington for decades, it also provided powder for competing ammunition firms.

After the transition from black to smokeless powders near the close of the nineteenth century, “MR” began appearing on cans of DuPont powders. It meant “military rifle.” The IMR line of “improved military rifle” powders came along in the 1920s when four-digit numbers replaced two-digit numbers in DuPont designations. MR 10 and kin were supplanted by IMR fuels, beginning with 4198. The first had relatively fast burn rates because in those days rifle cartridges were small. In 1934 DuPont introduced IMR 4227. It announced IMR 4895 in the early 1940s, specifically for the .30-06 in the M1 Garand. About that time the first “magnum” IMR propellant made its debut. Developed for 20mm cannons, 4831 would become one of the signature fuels for the big bottleneck rounds designed by wildcatters Roy Weatherby and P. O. Ackley.

Incidentally, powder numbers have nothing to do with burning rate. According to long-timer Larry Werner, powder from DuPont is labeled chronologically. High numbers indicate recent propellants. Those under development have traditionally been tagged “EX” for “experimental.” Larry, who started working with the company in 1954, recalls that “almost always, firearm design precedes cartridge design. Powder for a new round comes last. We’d start with a cookbook formula, then tweak the mix until we had it right.” Once a customer was satisfied “and committed to a batch of 5,000 pounds or so,” the “EX” was dropped from the designation and commercial labeling replaced it. Propellants made expressly for military use had no number prefix. “EX 7383 was developed for 50-caliber spotter rounds during the 1950s.”

Powder charts by DuPont and other companies help handloaders compare burning rates so they can choose an efficient powder for a given cartridge. “Closed bomb” tests are used to measure burn rate. A charge of powder ignited in a chamber of known volume produces a pressure curve that’s then compared to the curves from other propellants. But a powder’s behavior relative to that of other propellants can change, not only with changes in case capacity and bore diameter, but also with bullet weight. IMR assigns all its powders a Relative Quickness value. IMR 4350 has an arbitrary value of 100. According to Larry, fast-burning IMR 4227 has an RQ of 180; IMR 4198 comes in at 165 and IMR 3031 at 135. IMR 4064, 4320 and 4895 are listed at 120, 115 and 110, respectively, though some loading manuals suggest a different order. Savvy handloaders try a number of powders with similar burn rates to come up with a top load.

Rich McClure shot this half-minute group with 150-grain Hornadys, IMR 3031 in a Kimber ‘06.

DuPont’s old MR powders included single-base (nitrocellulose) and double-base (nitrocellulose with nitroglycerine) types. “All commercial ball powders are double-base,” explains Larry Werner. “Nitro delivers more energy per grain. It also reduces the tendency for grains to pick up moisture. Its drawback is residue. Double-base powders don’t burn as clean.” Larry adds that to get the full effect of nitroglycerine, you need 8 to 12 percent in the mix, but that some powders advertised as double-base contain less.

Heavy bullets in mid-capacity cases like the .30-06 call for powders like IMR or Hodgdon 4350.

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- CONTENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- SECTION I: BALLISTICS IN HISTORY

- SECTION II: THE MUSCLE BEHIND THE SHOT

- SECTION III: BULLETS—THE INSIDE STORY

- SECTION IV: SPEED, ENERGY, AND ARC

- SECTION V : PUTTING BALLISTICS TO WORK

- SECTION VI: FOR LONGER REACH

- BALLISTICS TABLES FOR MODERN SPORTING RIFLES

- GLOSSARY