5. Rifles from a Door Latch

Born in 1838 in the Swabian village of Oberndorf, Peter Paul Mauser did not succeed right away as a gun designer. His first project went nowhere. He and brother Wilhelm persevered to submit a viable infantry arm to the Prussian army. In 1872 the single–shot 11mm Mauser Model 1871 was accepted as the country’s official infantry arm. Its rugged turn–bolt action derived, legend has it, from Paul’s inspection of a door latch. Other governments took notice.

Mauser Bros. and Co. was founded in February, 1874. Following Wilhelm’s premature death, it became a stock company. In 1889 Fabrique Nationale d’Armes de Guerre (FN) was established near Liege to build Mauser rifles for Belgium’s military. The 1889 rifle, designed for smokeless–powder cartridges, confirmed Paul Mauser as the dominant rifle engineer in Europe. Over the next six years he improved the action. A staggered box magazine appeared in 1893. Two years later the Model 1895 incorporated most of the features that would make Mauser’s 1898 the top choice of ordnance officers from eastern Europe to the tip of South America. By the late 1930s, Mauser was selling rifles to sportsmen in the US through A. F. Stoeger of New York. At one time Stoeger listed 20 types of Mauser actions, differing not only in length (four were available), but in magazine configuration. These rifles didn’t come cheap. In 1939 retail prices ranged from $110 to $250. Since the second world war, modifications of Paul Mauser’s Model 1898 action have appeared in all the world’s game fields.

Peter Paul Mauser developed a single-shot 11mm Mauser Model 1871, soon accepted as Prussia’s official infantry arm. It featured a turn-bolt action.

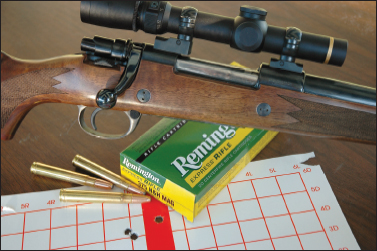

Buzz Fletcher built this lovely custom rifle on a 98 Mauser action. It’s chambered in .256 Newton.

The shift among American hunters to the centerfire bolt rifle began with their introduction to the Mauser–inspired 1903 Springfield. The Springfield’s fine accuracy and the reach of its .30-06 cartridge quickly won converts. Smokeless powder and jacketed bullets offered new possibilities to experimenters seeking better ballistic performance.

One of the most active cartridge designers during the Springfield’s heyday was Charles Newton. Educated as a lawyer, Newton designed the .250-3000 Savage, so named because its 87–grain bullet sped away at a reported 3,000 feet per second. He also fashioned, around 1912, the .25-06. With Fred Adolph, he designed other potent hunting cartridges. Newton started his own Newton Arms Company in August, 1914, intending to build his own rifles from DWM Mausers. Alas, his timing couldn’t have been worse: Germany went to war a day before the first shipment of Mausers was due. Not easily deterred, Newton designed a new rifle from scratch and loaded his own rounds (he even designed and built softnose bullets that would penetrate tough game). But he depended on Remington for brass. The first production run of Newton rifles was finished in January, 1917—just as America entered the war and the government seized control of all cartridge production.

A 1903 Springfield.

Again making the best of bad luck, Newton tooled up to make cartridge cases. But in August 1918, the banks supporting his venture sent it into receivership. He persevered with the Chas. Newton Rifle Corporation in April 1919. A deal with Eddystone Arsenal to supply equipment fell through, however, and Newton sold only a few rifles on imported Mauser actions. Later he formed the Buffalo Newton Rifle Corporation, which manufactured rifles of his design. It failed in 1929, shortly before Newton’s death.

More firmly grounded American gun companies began offering commercial bolt rifles soon after World War I. Remington’s Model 30 was followed in 1922 by Winchester’s Model 54. The versatile .30-06 proved the most popular chambering in both. In 1925 Winchester chambered its 54 for a new cartridge, the .270. Blessed with a receptive press, the .270 prospered. The .300 Holland & Holland Magnum, introduced at the same time, wooed some hunters, but its long case and belted head were not suited to standard–length military rifle actions. In 1937 Winchester replaced the Model 54 with the Model 70, destined to become the most popular centerfire rifle of the century. Chambered for every useful big game round, it had an action long enough to accommodate the .300 and .375 H&H Magnums. The strong Mauser–type extractor and a rugged but finely–adjustable trigger helped boost Model 70 sales.

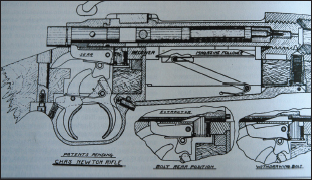

Charles Newton was a brilliant inventor—of both cartridges and rifles like this late bolt gun.

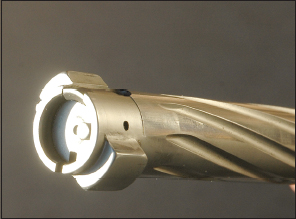

The two-lug Mauser bolt has evolved. McMillan rifles feature both fixed and plunger ejectors.

About this time, Charles Newton’s quest for more powerful hunting cartridges and innovative rifle designs was taken up by another experimenter. In 1937 insurance salesman Roy Weatherby moved from his native Kansas to California. To pursue his interest in firearms design, he bought a drill press and a lathe from Sears. He rebarreled or rechambered 1898 Mausers, 1903 Springfields, and 1917 Enfields to cartridges of his own design. His first publicized round, the .220 Weatherby Rocket, was a blown–out Swift. His next, the .270 Weatherby Magnum, became the first in a stable of fast stepping numbers on .300 Holland brass.

Nearly a century ago, Charles Newton developed rifles and cartridges far ahead of their time. The .30 Newton (right) and .256 Newton (actually a .264) sent bullets downrange as fast as do some modern magnums—despite the relatively primitive powders of that day.

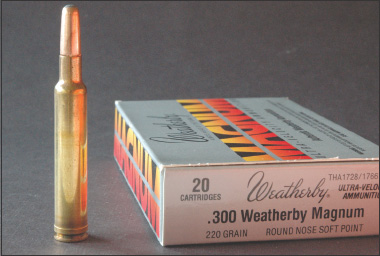

Weatherby soon made a business of his avocation, hawking high velocity as the path to lightning like kills at long range. His .270 Magnum drove a bullet 300 fps faster than a .270 Winchester. The .257 and 7mm Weatherby Magnums that followed were, like the .270 Magnum, based on a shortened Holland & Holland case to fit .30-06–length actions. The .300 Weatherby Magnum, a 1946 offering, had a full length case. All Weatherby rounds were distinguished by minimal body taper and a double shoulder radius. Roy marketed these cartridges (and the rifles he built for them) expertly, making sure that prominent politicians and movie stars were photographed with Weatherby products. In 1948 he standardized the Weatherby rifle, using a commercial Fabrique Nationale (FN) action. Ten years later he and company engineer Fred Jennie completed work on a new action they called the Weatherby Mark V. Its full–diameter bolt had nine locking lugs in three rows of three. The stock gave the rifle a futuristic look.

Remington briefly produced this Mauser-action sporter in .375. Wayne’s test rifle shot well!

During the last half-century, bolt–action rifles have changed little. The biggest shift, perhaps, has been in stock materials. Walnut has been replaced by hardwood like beech and birch in some instances but most commonly by synthetic materials. These range widely in quality, appearance, and fit. Detachable box magazines have become popular. So, too, stainless steel as an alternative to the traditional chrome–moly barrels and receivers. Iron sights have all but vanished as standard equipment, except on rifles intended for close shooting at dangerous game. Bolt–face extractors and plunger ejectors have largely replaced the stout Mauser claw and fixed ejector, but few shooters would say the 1898’s action has been improved. Some new actions are smoother and safeties are more scope–friendly. Still, Paul Mauser’s mechanism remains among the strongest and most reliable ever designed.

Roy Weatherby pioneered high-velocity wildcats on the Holland case. His .300 appeared in 1945.

Paul Mauser’s rifles saw dawn-to-dusk service in the African bush. Mauser-inspired rifles still do.

Roy Weatherby and his family.

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- CONTENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- SECTION I: BALLISTICS IN HISTORY

- SECTION II: THE MUSCLE BEHIND THE SHOT

- SECTION III: BULLETS—THE INSIDE STORY

- SECTION IV: SPEED, ENERGY, AND ARC

- SECTION V : PUTTING BALLISTICS TO WORK

- SECTION VI: FOR LONGER REACH

- BALLISTICS TABLES FOR MODERN SPORTING RIFLES

- GLOSSARY