29. Minding the angles

Most of the time, we shoot with the rifle held sights up, trigger down, at targets that allow the barrel to remain more or less horizontal. If we tip or cant the rifle so the trigger is no longer vertical, point of impact will change. It will also change if we fire at steep uphill or downhill angles.

“Canting isn’t bad,” a shooting coach told me long ago, “so long as you do it the same each time.” Doing it the same each time presupposes that you know you’re doing it in the first place. It’s quite easy to spot a cant if you’re coaching, just as it’s easy to see the tilt of a truck loaded heavily on one side if you’re driving behind it. In the truck’s cab, you might not be able to sense the lean of its bed; and when you’re looking through the sights you may be unaware of cant.

You may have thrown a pal’s rifle to your shoulder and found the reticle’s vertical wire is not even close to vertical.

“Good grief,” you say. “How can you shoot with the reticle tilted like that?”

“It’s not tilted.”

“Is too.”

“Is not.”

Such arguments can deteriorate quickly. One way to settle them is to lay the rifle in a rest or across sandbags, using one of the compact levels designed to help ensure squared-up rifles and reticles.

A canted reticle will not necessarily cause a miss. In fact, you can rotate the scope so the crosswire looks like an “X” and use it with deadly effect. The disadvantage is that you won’t have a vertical wire to help you correct for wind or show you the line of bullet drop at distance. You won’t have a horizontal wire to help you lead running animals.

A canted rifle, however, is another story. No matter how the reticle appears, if the rifle is tipped, you’ll have problems hitting beyond zero range because the bullet path is not going to fall along the vertical wire or directly below the intersection. If your sight-line is directly over the bore, a long shot requires you only to hold high. If the sight-line is forced by a canted rifle to the side of a vertical plane through the bore, you’ll not only have to hold high, but to one side. Here’s why:

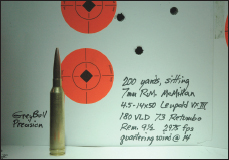

Sitting is a fine hunting position. Wayne shot this group at 200 yards with a GreyBull rifle.

How you support a rifle affects point of impact. Here an adjustable Caldwell rest cradles a Nesika.

Given that your scope is mounted directly above the bore, your line of sight crosses the bullet path twice. The first crossing happens at about 35 yards; the second is at zero range—say 200 yards. If the rifle is rotated so the scope falls to the side of the barrel, the sight-line crosses only once, because gravity sucks the bullet straight down, while the line of sight has a horizontal component. Put another way, whether the scope is on top of the rifle or a bit to the side, the line of sight will converge with the bullet path and slice through it, then angle away. If the scope is on top of the rifle, gravity pulls the bullet in an arc back into and through the straight line of sight. If the scope is not on top, the bullet’s path still dips below the horizontal plane; but the sight-line doesn’t follow it down. The rifle shoots to the side of where you look.

Prone is the steadiest position because it lowers center of gravity while increasing ground contact.

A cant that escapes your notice won’t cause a noticeable shift in bullet impact at normal hunting ranges. As the targets get smaller and the range longer, cant starts to matter.

When I shot on the Michigan State University rifle team, I marveled at a colleague who posted top scores but used a pronounced cant. In the offhand position, not only the line of sight but the rifle’s center of gravity fell near the centerline of his torso. Because he had time to position himself the same for each shot, and because the targets were all at a set distance, it proved no handicap at all.

Hunters don’t shoot at just one distance, however, or with adjustable stocks. So although a few degrees of cant seldom affect field accuracy, it’s a good idea to shoot with the sights squarely on top of the rifle. Cant is just one more thing to worry about, one more distraction, a small but thorny threat to the self-confidence that can help you shoot well.

Sometimes shooters slip a cant into their shooting routine without knowing it. They affix the scope carelessly, then subconsciously adjust the way they hold the rifle to correct for a tilted reticle. One culprit here is the ubiquitous Weaver Tip-Off scope ring. This inexpensive ring has been around a long time, and for good reason. It’s strong and lightweight. But because the top half hooks the base on one side and its two screws take up all the slack on the opposite side, tightening a Tip-Off ring can rotate the scope tube down toward the screws. If they’re installed on the right-hand side, you put a clockwise tilt into your reticle as you cinch them up. You may have aligned the reticle perfectly with the butt-plate before installing the ring tops, but now the crosswire is tipped! Solution: Back off the screws and twist the scope counterclockwise about as far as you think it moved. Tighten again, and check the reticle.

Offhand is an unsteady position—so merits practice! Chris shows how, with a Browning A-Bolt.

Canting isn’t the only way you can compromise your aim at long range. When I was growing up, side-mounted scopes were common. With them, you could attach a scope to a top-ejecting Model 94 or 71 Winchester, so you could use your iron sights and a scope without removing the scope. But a sight-line to the side of the receiver introduces the same error you get with a cant.

Top mounts centered above the bore can give you problems with sight angles too, if the bases are extra high. It’s easy to see this in exaggeration. Picture a scope with ring bases three feet high. If you adjust that scope to put its bullets on point of aim at 35 yards, you can’t expect a 200-yard zero. Sight-line now diverges quickly from the bullet’s trajectory, diving under it in a straight but steeply descending path. The bullet will eventually meet it, courtesy gravity, provided it doesn’t strike the ground first. The angle issue here isn’t a sideways tilt, it’s a steep forward tipping of the scope.

I once watched an elk hunter miss a huge bull from prone, with a rest. The range was perhaps 300 yards. He asked me where to hold, and I suggested high behind the shoulder, assuming his rifle was zeroed at 200. I checked it later, shooting to ranges of 400 yards. It was actually zeroed at 330. My client had fired it previously only at 100 yards, and someone had told him that bullets striking 3 inches high at 100 would be dead on at 200. Alas, the extra-high rings that put his Hubbel-size scope clear of the barrel set the line of sight at a steep angle to the trajectory, moving the second intersection of bullet arc and sight-line far away.

By far the most common questions about angles have to do with uphill and downhill shooting. The net effect on point of impact is essentially the same. As your shot deviates from the horizontal, the effect of gravity on the bullet over any given shot distance diminishes. That’s because gravity acts perpendicular to the earth; it’s always pulling things toward the earth’s center. Just as wind at right angles to a bullet has a greater effect on the bullet’s flight than wind coming from 7 o’clock, so gravity applied at right angles has its strongest influence.

For steep uphill or downhill shots, hold for the horizon component of the actual distance.

Imagine a bullet fired straight up, or one fired straight down through a hole deep enough to reach China. In both cases, gravity’s pull would act parallel to the bullet’s flight. Both bullets would fly straight until gravity and drag stopped them (Coriolis effect aside). You could argue that the bullet fired into the sky fights gravity immediately, while the bullet sent to China gets an initial boost from gravity. Truly, the effect of gravity on the nose and heel of bullets shot parallel with gravity’s pull is negligible at normal distances. The drag exerted on a speeding bullet is many times more powerful than the force of gravity.

When you shoot at any angle to horizontal, gravity’s effect is the same as you might expect if you considered only the horizontal component of the bullet’s flight. Say that you’re firing at a 45-degree angle at a deer 280 yards away. From geometry, you remember that a right triangle with one 45-degree angle has another also, and that the hypotenuse is roughly 1.4 times as long as either leg. In this case, the hypotenuse represents your bullet’s flight path in a triangle whose horizontal leg is the distance your bullet would cover if the target was moved vertically until it gave you a flat shot. That leg is the horizontal component of your bullet’s flight, whether you’re shooting uphill or down. If actual distance to the target at 45 degrees is 280 yards, the horizontal leg is roughly 200 yards. If you’re zeroed at 200, hold center. Shading high, as you would for a 280-yard shot on the horizontal, you’ll miss high.

You can determine effective range from the actual range if you know shot angle. The actual range is the hypotenuse of a right triangle whose horizontal leg is your effective range. If your math is a bit rusty, divide the actual range by these numbers:

| degrees angle | divisor |

| 10 | 1.02 |

| 15 | 1.04 |

| 20 | 1.06 |

| 25 | 1.10 |

| 30 | 1.15 |

| 35 | 1.22 |

| 40 | 1.31 |

| 45 | 1.41 |

The short magnums now include Winchester’s .325 WSM. It helped Wayne take this fine goat.

While Africa’s plains game doesn’t often impose steep angles, Lauri Homer shot this springbok uphill, and Wayne once killed a kudu by shooting almost straight down.

A lot of hunters overestimate the effect of shot angle. A useful rule of thumb: With most popular big game loads, don’t adjust aim for shot angle if the animal is closer than 200 yards, unless the angle is very steep— more than 45 degrees. When the shot is 300 yards, and the angle around 45 degrees, hold 6 inches lower than you normally would for a 300-yard shot. At 400 yards, hold a foot lower than you would for a horizontal 400-yard shot. Steeper angles require a little more adjustment, of course—I once bungled three shots at kudu that stood at 100 yards almost directly below me as I hung out over a bluff. Still, it’s not often that you’ll have to shoot long at angles of greater than 45 degrees. For gentle angles, keep your reticle on the animal and shade slightly for the reduced bullet drop.

Coaching from her tracker, and well-placed shooting sticks, help this huntress make a tough shot.

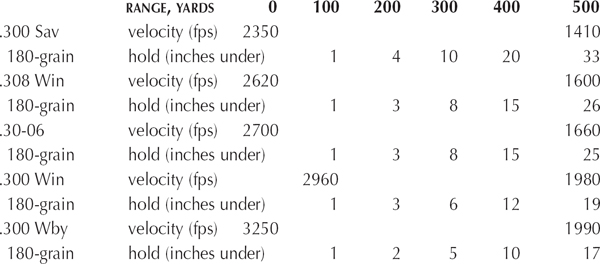

Flat-shooting cartridges offer a bonus if you’re not shooting horizontally:

Adjustments in aim for targets at 45 degrees to horizontal

Truly, errors caused by cant and steep shot angles pale beside those resulting from rifles that move as the bullet leaves. Holding a rifle steady and executing a shot smoothly still matter most.

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- CONTENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- SECTION I: BALLISTICS IN HISTORY

- SECTION II: THE MUSCLE BEHIND THE SHOT

- SECTION III: BULLETS—THE INSIDE STORY

- SECTION IV: SPEED, ENERGY, AND ARC

- SECTION V : PUTTING BALLISTICS TO WORK

- SECTION VI: FOR LONGER REACH

- BALLISTICS TABLES FOR MODERN SPORTING RIFLES

- GLOSSARY