3. Rifles for a Frontier

In his father’s forge on Staley Creek, four miles from the Mohawk River, Eliphalet (“Lite”) Remington pumped the bellows. When the rod he had chosen for the barrel of his first rifle glowed red, he hammered it until it was half an inch square in cross-section. Then he wound it around an iron mandrel, heated it again until it was white-hot and sprinkled it with Borax and sand. He held one end with his tongs and pounded the other on the stone floor to seat the near–molten coils. After it cooled, Lite checked it for straightness and hammered out the curves. Then he ground and filed eight flats on the .45–caliber tube, because octagonal barrels were popular. Lite traveled to Utica to pay a gunsmith four double reales (about $1 in country currency, when $200 a year was a living wage) to rifle the .45–caliber bore. That took two days. Returning home, Remington bored a touch-hole and forged a breech plug and the lock parts. He shaped them with a file, then brazed the priming pan to the lock plate. He used uric acid and iron oxide, a preservative known as hazel brown, to finish the steel. Lite fashioned the walnut stock from scratch with draw-knife and chisel. He smoothed it with sandstone and sealed it with bees-wax. Hand–made screws and pins joined the parts.

The year was 1816. Lite Remington promptly took his new rifle to a local shooting match. He placed second. So impressed was the match winner that he asked if Lite would build a rifle for him. Lite agreed to deliver one in 10 days for $10.

As the US frontier edged south and west, hunters found their needs changing. Grizzly bears and bison didn’t fall to the light charges fired from svelte Kentucky rifles. Neither were long barrels and fragile stocks ideal for hunting on horseback. While Daniel Boone was probing the Cumberlands in the late 1700s, gun makers began re-configuring the Kentucky rifle. They made it sturdier and gave it iron hardware and a bigger bore. The result: the “mountain” or “Tennessee” rifle. During this transition in rifle design, General W. H. Ashley, head of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, promoted the rendezvous as a way to collect furs from trappers in the West. Tons of pelts funneled from frontier outposts to St. Louis. Among the many Easterners seeking fortunes in Missouri, then gateway to the West, was gunsmith Jacob Hawkins. In 1822 his brother Samuel closed a gun shop in Xenia, Ohio to join Jake. The two changed their name to the original Dutch “Hawken” and started building rifles.

The Hawkens rifle was the plains rifle of choice in the 1800s.

The flint lock comprises a frizzen (here open), a pan, and a hammer holding flint. The percussion lock, more reliable, employs a primed copper cap on a short tube. A hammer blow ignites the cap.

As Youmans in North Carolina had become a pre-eminent maker of Tennessee rifles, the Hawken brothers would define the plains rifle. It borrowed from Youmans’ design but had a shorter, heavier barrel for horseback carry and to accommodate bigger powder charges. The full length stock was replaced by a half-stock, typically maple with two. The traditional patch box was often omitted. Until 1840, the standard firing mechanism was a flintlock, sometimes purchased, more often fabricated in house. The Hawkens used Ashmore locks as well as their own, and typically installed double–set triggers. A typical Hawken weighed just under 10 lbs, with a 38 inch, .50–caliber octagonal barrel made of soft iron with a slow rifling twist. Hawken barrels were less susceptible to fouling problems than the hard, quick twist barrels common to “more advanced” English rifles of the day. They retained traces of bullet lube and delivered better accuracy with patched round balls. Other makers—notably Henry Lehman, James Henry, George Tryon—produced plains rifles that looked like (and in some cases were patterned after) Hawkens.

Hunters with Hawken rifles reported kills at 200 to 300 yards, long shooting in those days. Charge weights typically ran 150 to 215 grains. Bore size increased as lead became easier to get and buffalo more valuable at market. In an article for the Saturday Evening Post (February 21, 1920 as cited by Hanson in “The Plains Rifle”), Horace Kephart wrote of finding a new Hawken rifle in St. Louis:

The Kentucky rifle was a common weapon on the American frontier.

“ … It would shoot straight with any powder charge up to a one-to-one load, equal weights of powder and ball. With a round ball of pure lead weighing 217 grains, patched with fine linen so that it fitted tight, and 205 grains of powder it gave very low trajectory and great smashing power, and yet the recoil was no more severe than that of a .45-caliber breech loader charged with 70 grains of powder and a 500–grain service bullet …”

In 1849, when the California Gold Rush began, you could buy a Hawken rifle for $22.50. That year Jake Hawken died of cholera. Sam continued building and repairing rifles alone. In 1859 he made his first trek to the Rocky Mountains, where many of his rifles had gone. Sam apparently worked in Colorado mines for a week, then started back to Missouri, where upon his return he was quoted as saying “ … and here I am once more at more at my old trade, putting guns and pistols in order ….”

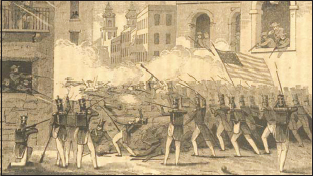

William Stewart Hawken, Sam’s son, rode with Kit Carson’s mounted rifles. He was wounded during the Battle of Monterey, September 23, 1847, when he and a small group of frontiersmen fought to hold a bridge over San Juan Creek. Vastly superior numbers gave Mexico the victory. The clash left only nine ambulatory men among 43 Texas Rangers. William Hawken, age 30, made his way back to Missouri.

The Battle of Monterrey was a turning point in the Mexican-American War.

When Sam went west he left William in charge of the Hawken facility. William got this letter:

Evans Landing Nov. 27th 1858

Mr. Wm. Hawkins

Sir, I have waited with patience for my gun, I am in almost in a hurry 2 weeks was out last Monday I will wait a short time for it and if it don’t come I will either go or send. If you are still waiting to make me a good one it is all right. Please send as soon as possible.

Game is plenty and I have no gun. Yours a friend.

Daniel W. Boon.

After his return to St. Louis, Sam Hawken hired a shop hand. J. P. Gemmer had immigrated to the US from Germany in 1838. He proved capable and industrious and in 1862 bought the Hawken enterprise. He may have used the “S. Hawken” stamp on some rifles, but marked most “J. P. Gemmer, St. Louis.” Sam Hawken continued to visit his shop in retirement and once built a complete rifle. He outlived Jim Bridger and Kit Carson and many other frontiersmen who had depended on Hawken rifles. When he died at age 92 the shop was still open for business! It closed in 1915; J. P. Gemmer died four years later.

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- CONTENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- SECTION I: BALLISTICS IN HISTORY

- SECTION II: THE MUSCLE BEHIND THE SHOT

- SECTION III: BULLETS—THE INSIDE STORY

- SECTION IV: SPEED, ENERGY, AND ARC

- SECTION V : PUTTING BALLISTICS TO WORK

- SECTION VI: FOR LONGER REACH

- BALLISTICS TABLES FOR MODERN SPORTING RIFLES

- GLOSSARY