18. Inside an ammo factory

Dave Emary, chief ballistics engineer, has been behind much of the innovation at Hornady. Like many of the company employees, he’s an active shooter. In fact, he’s an accomplished high-power rifle competitor and was even named to the President’s Hundred at Camp Perry. Before coming to Hornady, he worked with artillery, “shooting 5-lb bullets at 7,000 fps and 12-lb bullets at 6,500” from 90mm and 120mm cannons. Expertise he acquired in the armed forces has helped him design 25-grain 17-caliber spitzers and 500-grain .458 solids for sportsmen.

Dave explains that Hornady gets its lead in ingots, which are melted and formed into cylindrical blocks about the size of a roll of freezer paper (but heavier!). A massive press squirts these cylinders, cold, through dies to form the lead wire that’s cut into bullet lengths. Antimony content is specified at purchase, from 0 to 6 percent. More antimony means a harder bullet. Most bullet cores have 3 percent antimony.

Jacket cups are punched out of sheets. “Jacket uniformity and concentricity are vital to accuracy,” Dave says. “We hold concentricity to .003.”

Hornady’s Spire Point softpoints have been a mainstay of big game hunters for decades. Now the firm also makes A-Max (Advanced Match Accuracy) spitzers for competitive shooting. V-Max bullets, introduced in 1995, share the A-Max’s plastic nose insert. They’re designed with thin jackets for explosive effect on small animals. The SST (Super Shock Tip) plastic-nose bullet for big game followed. “We got the SST designation from an old 1950s Hornady bullet board,” explains Dave.

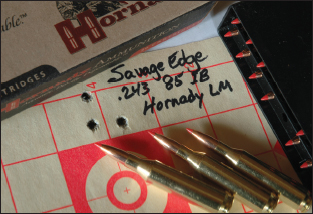

Inexpensive rifles with good ammo can shoot well! Here: a Savage Edge, Hornady InterBonds.

Hornady has successfully mined niche markets too. After someone found the .50 BMG would detonate dynamite at 1,000 yards, this military round got lots of attention. When Hornady announced its A-Max bullet for the big .50 in 1994, it sold briskly. Its sleek profile and long aluminum tip kept weight to the rear for best accuracy. A ballistic coefficient of over .600 gave shooters the flat flight they wanted.

“We tried aluminum tips on 162-grain 7mm bullets as well,” recalls Dave Emary. “They worked but proved too costly. We replaced them with a long plastic tip, but that gave erratic accuracy.” The firm then switched to small plastic tips (all Hornady red) in both match and hunting bullets, refining the nose contours when necessary. These produced small groups consistently, partly because the tips were easier to manufacture to uniform dimensions, partly because the bullets come out a bit shorter and were thus less finicky about rifling twist. Aluminum is now used only in A-Max .50s.

Hornady bullets reflect Dave’s experience at the 1,000-yard line. He points out that bullet design is an exercise in compromise. “Though it would reduce drag in the barrel, lengthening the nose to shorten the shank gives the nose greater leverage if it swings off the bullet’s axis in flight,” he says. A long nose also mandates a more gradual curvature forward of the shank, which increases odds for bullet misalignment in the throat, and for subsequent yaw. “A short transition is usually best, so the bullet is forced quickly into full contact with the rifling.” Dave says he likes to keep the ratio of bullet bearing surface to diameter at 1.5 or higher, though nose type and other variables also affect that ratio.

Some shooters might question the need for new softpoint bullet designs, given the broad selection available from Hornady and other makers. Even at the sprawling Grand Island plant, there are too many to make at once. “Contrary to what many shooters think,” says Steve Johnson, who represents Hornady to the press. “We can’t forever dedicate one machine to, say, 200-grain .338 bullets. We run enough to build up our stock, then switch to another bullet on that machine.” Batch size depends on market demand. Hornady production lines stay busy supplying handloaders and the company’s own loading machines—but also other ammunition firms that feature Hornady bullets. “We just finished a run of two million FMJ bullets for Federal,” Steve pointed out during one visit. “We make V-Max and boat-tail softpoints for Remington. In fact, we’ve manufactured bullets for every major ammo firm.” Those lack the Hornady label.

Development of new bullets and ammunition requires extensive testing—and instruments like the sophisticated Heise Gauge. It’s a hydraulic device for calibrating chamber pressure. A transducer with a quartz crystal registers pressure through electrical discharge, explains Dave Emary. He says peak pressure as commonly measured in copper units (CUP) tells little about the pressure curve. “Time matters. You can boost velocity by extending the peak of the curve forward without making the curve higher.” He says that a strain gauge falls short because it can’t be calibrated to a standard in the manner of the Heise. Dave allows that handloaders get adequate indication of high pressure by measuring web expansion. “But it’s crucial that you mike all cases at the same spot, because a .001 bulge at the web can become .005 a touch farther forward. It’s best to measure forward, because you get more reaction from the brass.”

He adds that handloaders will notice pierced primers at 70,000 CUP, and blow cups at 80,000. Pressure that’s high enough for most shooters to notice is already well above SAAMI spec. “We got higher speed from our Light and Heavy magnum ammo by pushing the pressure curve forward so the peak occurs when the bullet is 3 inches out. That powder has about 4 percent more nitroglycerin than ordinary double-base powders. Surface deterrents slowed the initial burn so the bullet didn’t outrun the burn so soon.”

Ammunition has become a bigger part of Hornady’s business plan. “We launched Light Magnum ammo in 1995,” recalls Dave, “after I saw at Olin-St. Marks how super-powerful loads could be concocted in ordinary cases, using new propellants that kept a lid on pressures.” But those ball powders had to be compressed, hiking cost of manufacture. The stiffer charges also increased recoil. And some cartridges didn’t lend themselves to turbo-charged loads. But many did, and the ballistic boost was often impressive: 150 fps at the muzzle. The Light Magnum line came to include several popular rimless rounds—and the .303 British. “The .303 has a great record on game,” Dave says. “And we still get lots of orders for 174-grain FMJs from Australia.” The Light Magnum load features a 150-grain Spire Point bullet at 2,830 fps. Hornady’s .458 Heavy Magnum kicks a 500-grain bullet downrange at 2,300 fps. At this speed, the bullet hits harder than one from a .470 Nitro Express, yielding 15 percent more energy than ordinary .458 loads.

All told, Hornady’s Light Magnum and Heavy Magnum (belted) rounds proved a good move, and Steve continued to look for other opportunities in the ammunition field.

“The .17 HMR wasn’t on our radar,” he concedes. “But Dave had worked out many of the early problems with sub-caliber rimfires. We had so much fun with that .17, I called Darrell Inman at CCI to see about loading it. Darrell told me I had to order five million cartridges and pay for the tooling! It was a dare. I took it.” Weeks after its introduction, sales of the .17 Hornady Magnum Rimfire shot past the first year’s projections. Hornady doubled its order for cartridges (still the only ones to bear the Hornady name). When in 1998 I reported on the first .17 HMR rifles, ammo back-orders totaled 12 million rounds!

The company went a step beyond load development when in 2001 it fashioned a new varmint round: the .204 Ruger. Sales of three million 33-grain bullets for the .20 Tactical had hinted of strong interest in sub-.22s. With Ruger, Hornady assembled a lightning-fast load in a modified .222 magnum case, a 32-grain V-Max .204 bullet at 4,200 fps. Negligible recoil allowed riflemen a look at bullet impact. In conjunction with Ruger, Hornady also developed .375 and .416 Ruger cartridges, then .300 and .338 Ruger Compact Magnums—these two specifically for short-barreled rifles. The .450 Bushmaster for AR-type rifles came from Hornady’s shop, and the .30 TC, for Thompson/Center. Hornady warmed to the task of loading such obscure numbers as the 9.3x74 R. It loads the 6.5 Grendel, the 6.8 SPC, the .376 Steyr, the 9.3x62, the .458 Lott. There’s a .44-40 Cowboy load and both solid and softpoint ammunition for classic African rounds: the .404 Jeffery and .416 Rigby, the .450/400, .450, .470 and .500 Nitro Express. Hornady offers hunting loads for burly handgun rounds, from the .44 Magnum to the .476 Linebaugh and .500 S&W. Tactical and its own Critical Defense lines of rifle and pistol ammo complement what has become the company’s most celebrated development to date: LeverEvolution ammunition.

This Ruger Hawkeye is carbine-quick, but the .300 RCM performs efficiently in its short barrel.

It sprang in part from Dave Emary’s growing interest in old lever rifles. Like other enthusiasts, he bemoaned the blunt bullet noses required in tube magazines to prevent accidental ignition when recoil jarred the stack. Blunt bullets traced steep arcs, limiting effective range. Dave tackled this problem with a resilient polymer bullet nose that would yield to sudden pressure, then spring back into aerodynamic shape when that pressure was released. Now streamlined bullets could be carried safely in lever-actions! Ballistic coefficients for the new .30-30 and .35 bullets were 20 percent higher than for blunt bullets. Hornady did not stop there. A “Light Magnum”.30-30 load clocking 2,400 fps challenged the .300 Savage. At 250 yards, the 160-grain .30-30 spitzer hit half again as hard as flat-nose bullets from ordinary .30-30 loads.

Hornady quickly added the LeverEvolution Flex-Tip or FTX bullets to other traditional lever-rifle cartridges. The line came to include not only such rounds as the .32 Special and .45-70, but more modern numbers like the .444 and .450 Marlin and, eventually, handgun cartridges like the .357 and .44 Magnums. Next step: Marry the FTX bullet and new, efficient powders in a more potent cartridge for lever-actions.

Dave Emary developed the .338 Marlin Express. Wayne has used this rifle on targets to 600 yards.

Dave Emary came up with the .308 Marlin Express, matching the ballistic muscle of the defunct but potent .307 Winchester. “It carries .300 Savage punch in a semi-rimmed case,” he said. But pressures above 47,000 PSI didn’t seem appropriate in traditional lever rifles. “So we throttled back to 46,500. No troubles.” The 160-grain FTX developed for the .30-30 flew more accurately than the 165-grain spitzer intended for the new round. “The final rendition was a 160 with a long ogive, the Interlock band pushed forward boost weight retention. A .395 ballistic coefficient gave it great reach. Exiting at 2,660 fps from the .308 Marlin Express, it clocks over 2,000 at 300 yards.

Hornady’s LeverEvolution line now includes cartridges like the .357, used in Marlin’s 1894 rifle.

That fall, I shot the first elk to fall to the .308 ME, a New Mexico six-point.

Never one to sit still, Dave told me he planned to develop a lever-action round to trump all others, “one that equals the .30-06.” With Mitch Mittelstaedt and other colleagues, he settled on a .33 bore. You could say Federal beat him to the punch. But the excellent .338 Federal—a .308 necked up—was designed for bolt actions, not rear-locking lever rifles. Dave and Mitch settled on the .376 Steyr hull as a model but changed the hull, beefing up the web. Loaded with a new 200-grain FTX bullet, the.338 Marlin Express is 2.60 inches long. At 2,565 fps, muzzle velocity matches that of the .348 Winchester’s 200-grain flat-nose, then leaves it behind. The .338 ME bullet can’t deliver the muzzle energy of the heavier (325-grain) .450 Marlin. But at 100 yards they’re equals, and beyond that, the ballistically superior .338 takes over. It hews closely to the arc of a 210-grain Partition from the .338 Federal. At 400 yards, the payloads of 200-grain .338 ME and 180-grain .30-06 bullets are essentially the same: 1,760 ft-lbs.

While raising the bar on lever-rifle performance, Hornady was also developing new bolt-action rounds. Mitch Mittelstaedt worked with Dave in adapting new propellants to cartridges designed for short-action carbines. “Typically we sacrifice 160 fps when we chop a .30 magnum barrel from 24 to 20 inches,” Mitch explained. “The .300 and .338 Ruger Compact Magnums leak only 100 fps in 4 inches.” On a range with chronograph guru Ken Oehler, I set up one of his fine 35P instruments to check bullet speeds in Ruger rifles with 20 inch barrels. Three 180-grain .308 SST bullets averaged 2,840 fps. The Ruger in .338 RCM sent 225-grain softpoints out the muzzle at 2,675 fps. Groups measured just over an inch.

“The RCMs are really short versions of the .375 Ruger,” Mitch told me. The .300 and .338 cases have .532 rims, mike 2.100 and 2.015, base to mouth, and are both loaded to 2.840-inches. “We designed the .338 hull to accept current .33 bullets,” he said, “most of which were fashioned for the .338 Winchester. A 2.100 inch case would have put the mouth in front of cannelures and beyond the shanks of some bullets.”

Amazingly, these powerful, efficient RCM loads didn’t last long. Two years after their debut the company announced they’d be replaced. “We’re dropping them in favor of Superformance loads that add nearly 100 fps,” Steve Johnson confided to me. “We’ll abandon the Light and Heavy Magnum lines too.”

Sensing something important, I pressed him for details.

“Dave and his crew have found a way to apply what they’ve learned from LeverEvolution and the Marlin Express and RCM cartridges to ordinary ammunition. They’re getting higher speeds under SAAMI pressure limits. We don’t compress the powder. We’re losing just 18 fps per inch of barrel when we whittle a .300 Winchester to carbine length. And it behaves the same at 15 below as at room temperature….”

More speed, more energy, standard pressures—new powders fuel Hornady Superperformance ammo.

Hornady’s Superformance ammunition is truly a major industry development. Dave Emary calls it the most significant hike in centerfire performance since standards were set with IMR propellants in the 1930s. Steve Hornady looks me straight in the eye and declares: “No other sporting ammo can come close. Superformance delivers higher speeds, flatter flights, less recoil and lower pressures than its competition. It’s as accurate as any ammo we’ve ever produced, less temperature-sensitive and more efficient in short barrels. It retails for less than cartridges souped up with compressed charges.”

Still young at this writing, Superformance ammunition already comprises 28 loads, from 95-grain .243 to 225-grain .338 Winchester Magnum. All share feature ball powders chemically and physically treated to deliver that smooth, steep but flat-topped pressure curve that pushes bullets quickly from the case, accelerates them smoothly down the bore, then drops off decisively. Low muzzle pressure, even in short barrels, means you get less blast; and less energy is wasted at exit. “Superformance loads match the ballistic thrust of Light and Heavy Magnums, but with charges 10 to 15 percent lighter,” says Dave Emary.

Alice van Zwoll loads up with Hornady Superperformance ammo, which delivers higher velocities.

Steve Johnson adds: “Our tests show Superformance ammo delivers an increase of 100 to 300 fps over standard. In a Model 70 .270 with a 22 inch barrel, Superformance 130-grain loads gave us 3,100 fps, while same-weight bullets from two other ammunition makers clocked 2,920 and 2,780.”

Tested in temperatures from -15 to 140 degrees F confirm that Superformance powders don’t care a great deal about the weather. Some loads show no velocity change from room temperature to below zero, according to Dave. He says all demonstrate greater consistency than traditional loads. “We’ve even found them to show less sensitivity to variations in bore diameter.”

The propellants in Superformance ammunition are not available to handloaders. Manufactured by St. Marks in Florida (home of Winchester ball powders, now sold in canisters by Hodgdon), they endure chemical tweaks and degrees of crushing to meet defined burning characteristics. “We do some blending of powders here at Hornady,” smiles Steve Johnson. “Anyone trying to duplicate our efforts or back-engineer our propellants would take two years doing so. We’re not worried.”

In sum, Hornady Superformance ammunition is that rare product with no obvious flaws. It drives bullets significantly faster at pressures below SAAMI limits, while maintaining high levels of accuracy. It behaves consistently over a broad temperature range. It even costs less at the counter—just a dollar or two more than ordinary ammo, and $5 or so less than the current crop of hyper-velocity rounds.

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- CONTENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- SECTION I: BALLISTICS IN HISTORY

- SECTION II: THE MUSCLE BEHIND THE SHOT

- SECTION III: BULLETS—THE INSIDE STORY

- SECTION IV: SPEED, ENERGY, AND ARC

- SECTION V : PUTTING BALLISTICS TO WORK

- SECTION VI: FOR LONGER REACH

- BALLISTICS TABLES FOR MODERN SPORTING RIFLES

- GLOSSARY