31. Faster and shorter

In the 1890s, long, blunt military bullets in cases of modest capacity gave riflemen their first shooting with smokeless powder. The 7x57 launched a 173-grain bullet, the .30-40 Krag a 220-grain, the .303 British a 215-grain, the 8x57 (then the 7.9x57) a 226-grain. All traveled at roughly 2,200 fps from long barrels. When streets were still mostly dirt and our Civil War still sharp in collective memory, 2,200 fps was pretty fast.

But fast didn’t stay fast. When Germany announced a new 154-grain bullet for its 8x57 cartridge in 1905, it raised the standard. This missile had a pointed nose and left the muzzle at a scorching 2,880 fps. Not to be outdone, the US scrapped the 220-grain .30-03 bullet (adopted from the Krag) and replaced it with a 150-grain spitzer. Velocity: 2,700 fps. Both countries made other changes in their service cartridges at that time. Germany increased bullet diameter from .318 to .323, the present diameter of 8mm bullets. A “J” was used to designate the original round (J meaning I for infantry), and an “S” (for Spitzgeschoss; also JS or JRS) given to the new one. American ordnance people shortened the .30-03’s case .07, then renamed it the “Ball Cartridge, Caliber .30, Model 1906.”

Other nations also recognized the advantages of pointed bullets moving fast. Flat trajectory made precise range estimation less critical and hitting easier. By the time the Archduke Ferdinand was felled by an assassin, most countries had rifles that far outstripped their sights. The .30-06 was claimed to be lethal at 4,700 yards, farther than most doughboys could keep ‘06 bullets on the side of a commercial granary. Still, like arrows loosed en masse at Agincourt, a volley of bullets raining on distant enemy positions was bound to be felt. Effective range and the range at which a soldier could hit a single combatant were quite different!

This pronghorn fell at 300 yards to a shot from Dave Anderson’s .257 Weatherby Magnum.

Wayne got this moose with a single Hornady GMX bullet from his Ruger Hawkeye in .300 RCM.

Small-arms reach became important to generals trying to conserve their troops under the withering artillery fire cratering battle-fields farther and farther from the cannon’s mouth. So it was with consternation that in battle they found the 150-grain .30 Springfield bullet mostly useless beyond 3,400 yards. So the US changed its service bullet again, this time to a 173-grain spitzer with 9-degree boat-tail and long, 7-caliber ogive (radial curvature between shank and tip). Muzzle velocity dropped—but not much. This new “M1” bullet, issued in 1925, left the barrel at 2,647 fps. Its higher ballistic coefficient carried it 5,500 yards!

In 1939 the Army went back to a lighter bullet, a 152-grain spitzer designated the M2. The reason for this switch was the brutal recoil delivered by the M1 load. Even at 2,805 fps, the 152-grain bullet was easier to shoot. Like the M1, it had a gilding metal (zinc and copper) jacket to prevent metal fouling. With the M2 we fought the second world war. …………….

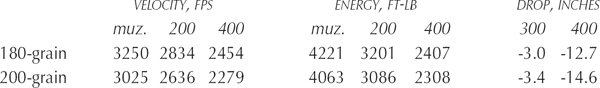

Modern hunting bullets resemble the pointed German infantry bullets of 1905. About the only blunt bullets still popular are for heavy African games shot up close, where sectional density matters most. Oddly, hunters often talk about weight as if it were the crucial variable. To show how small a difference bullet weight can make in killing game, here’s a look at two Nosler Partition bullets in the .300 Ultra Mag (zero: 250 yards).

Either would work fine on the big game for which this cartridge was designed. The relatively even rate of velocity loss shows these bullets have nearly identical ballistic coefficients (.474 to .481). There’s negligible difference in bullet drop to 300 yards, and the 2 inch disparity at 400 is just half as great as the bullet dispersion from a minute-of-angle rifle. It surely doesn’t matter when you’re shooting at a moose. The edge in velocity enjoyed by the 180 is offset by the greater mass and sectional density of the 200.

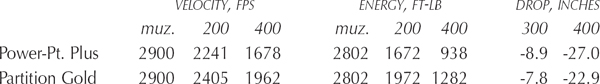

Another comparison worth a look is between bullets of the same weight but different nose shape. These two Wincheseter 150-grain .308 loads both clock 2,900 fps at the muzzle:

You might choose a Partition Gold bullet over a Power Point on the basis of this chart—and forget that most big game is shot closer than 200 yards, where either bullet would kill quickly. Accuracy counts for something, and maybe the Power Point Plus load shoots better in your rifle. I once chose a Power Point bullet over a Nosler Partition for an elk hunt simply because the Power Point gave me exceptionally tight groups. I killed a bull with one shot. If you expect close shots at tough game you’ll want the Partition for its penetrating qualities, not for its flatter flight.

L-R: the .308, .243, and .358 all appeared in the mid-fifties. The .260, 7mm-08 and .338 Federal followed, on the same case. Short-action rifles were proportioned for this family of cartridges.

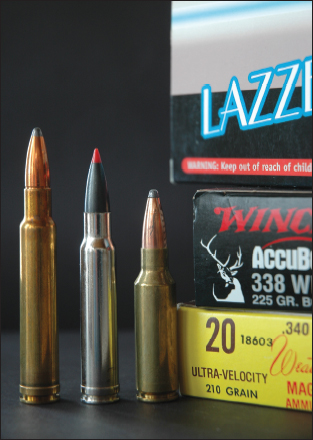

Case size used to indicate relative performance. Not anymore, Remington’s .300 Ultra Mag merely matches Weatherby’s load for its .300 Magnum, though the Ultra Mag has 13 percent more case capacity. As capacity increases, efficiency drops. The .30-378 Weatherby Magnum and 7.82 Lazzeroni Warbird hit just a little harder than the .300 Weatherby, which gets almost equal velocity from 20 percent less powder.

Hiking bullet velocity once required adding powder and enduring more recoil. But some shooters have worked hard to wring high speed from compact cartridges that don’t kick hard. In 1974 benchrest competitor Dr. Lou Palmisano reshaped the .220 Russian round to form what he and cohort Ferris Pindell would call the .22 PPC. A 6mm PPC came later. These cartridges were short and squat. From the base to the 30-degree shoulder measured barely over an inch, though basal diameter approached that of the .30-06. Palmisano thought a shorter powder column would yield better accuracy. In benchrest matches, where quarter-minute groups are commonplace, the PPC would have a tough test. The .222 Remington and 6x47 (a necked-up .222 Magnum) had been the darlings of serious competitors long enough that they held most of the records. Their popularity also meant that the “triple deuce” and 6x47 were chambered in the best rifles and used by the most competent riflemen. The PPC not only had to be superior; it needed time in the hands of shooters who didn’t like to lose points experimenting, who might replace a barrel to try a new round but would be a lot more reluctant to change the bolt face on their pet bench rifle.

Palmisano and Pindell were convinced that the PPC case had promise. Soon their champion-level shooting and careful handloading produced winning groups. Other shooters followed. In the 1975 NBRSA championships, two of the top 20 shooters in the sporter class used PPCs. By 1980, 15 of the top 20 were so equipped. In 1989 all of them used the short, fat rounds. Even more impressive: The top 20 entrants in the demanding Unlimited class shot PPCs. And 18 of the 20 best in Light Varmint and Heavy Varmint categories favored them. Sako eventually chambered rifles for the PPCs, but despite vigorous campaigning by Palmisano, American gun companies demurred. The East Coast physician then took it upon himself to supply the benchrest community with PPC brass, importing more than a million .220 Russian cases! At this writing, 35 years later, the short, squat profile of the PPC has become commonplace in hunting camps.

Rick Jamison and John Lazzeroni pioneered the short powder column in big game rounds, albeit John is perhaps best known for his long magnums. Ballistically, his rimless 7.82 Warbird rivals the .30-378 Weatherby. His 8.59 Titan matches the .338-378. Lazzeroni’s long cartridges range in caliber from 257 to 416. The cases are of his own design and manufacture. “If I’d done my homework,” admits John, “I might have based them on the .404 Jeffery. Head dimensions of my rounds are ridiculously close to the .404’s.”

L-R: The 6.5 Creedmoor’s hull is a tad shorter than the .260 Remington’s, to accept longer bullets.

The Lazzeroni short magnums have the same heads, just .750 less case up front. The heads for his .243 and .264 short cartridges mike .532, same as for an ordinary belted magnum like the 7mm Remington or .300 Winchester, and identical to the head on Lazzeroni’s long .257 Scramjet. The short 7mm, .300, .338 and .416 Lazzeronis feature .580 heads, like their longer counterparts. There used to be a .264 and a 7mm on a .546 case, but John discontinued them. He dropped the long .264 altogether and revived the 7mm on a bigger case. John lists these velocities for his compact versions:

6.17 (.243) Spitfire: 85-grain bullet at 3618 fps

6.71 (.264) Phantom: 120-grain bullet at 3312 fps

How to get rifle performance from a handgun? Use a strong rifle action, as Remington did by adapting the M600 bolt mechanism to its XP-100 pistol. Note the cantilever design, action to the rear, that allows a long but balanced barrel.

The 8.59 Galaxy (a .33) is Wayne’s favorite among a handful of short, potent Lazzeroni magnums.

7.21 (.284) Tomahawk: 140-grain bullet at 3379 fps

7.82 (.308) Patriot: 180-grain bullet at 3184 fps

8.59 (.338) Galaxy: 225-grain bullet at 2968 fps

10.57 (.416) Maverick: 400-grain bullet at 2454 fps.

These cartridges are short enough to fit .308-length rifle actions. Of course, the magazine and bolt face must be altered for the fatter case. Or you can buy John’s rifle, the L2000SA. Appropriately dubbed the Mountain Rifle, it weighs only 6 ½ lbs. The McMillan action gets the same treatment as on long-action models: oversize Sako-style extractor, custom bottom metal, three-position safety, fluted Schneider cut-rifled barrel and Jewell trigger. John bores out the standard 6-48 scope mount holes, then drills and taps them to 8-40 for dead-center spacing and a more secure hold. Except for the magazine spring, all steel in this Lazzeroni rifle is stainless, jacketed with a satin-silver NP3 electroless nickel finish. It wears a classic-style synthetic stock, with a long, slender grip, straight comb, sharp checkering and a soft buttpad.

This Lazzeroni rifle is comfortable to shoot, partly because of the case shape. According to John, a squat hull “concentrates powder around the primer, so ignition at the front of the column occurs faster. Less powder starts moving with the bullet. Since powder following a bullet out the case mouth is ejecta, the less you send down the bore, the better. Recoil reflects both the burned and unburned weight of heavy charges.”

Short cases give you the option of using faster fuel. John loads RL-15 behind 225-grain bullets in the Galaxy to get 2,760 fps—velocity you’d expect from the longer .338 Winchester and H4350.

Short Lazzeroni cartridges preceded Winchester’s 2001 announcement of stubby rimless .30 with a .532 base. Slightly longer than the Lazzeroni Patriot, the .300 Winchester Short Magnum duplicates its performance. That is, it shoots as flat and hits as hard as a belted .300 Winchester Magnum. But with an overall length of 2.76 inches, it’s half an inch shorter than the .300 Winchester. In fact, a .300 WSM cartridge is shorter than the hull of a .300 H&H, granddaddy of all belted magnums. And out-performs it.

Actually, Browning approached Winchester with the idea for a short .300 magnum early in 1999. Winchester ammunition engineers finalized the dimensions. Browning and US Repeating Arms Company (USRAC, manufacturer of Winchester firearms) redesigned their flagship bolt rifles—the A-Bolt and the Model 70—for the .300 WSM. Winchester followed with short .270 and 7mm rounds on the same case. Increasing bullet diameter proved problematic, given the ogive of .338 bullets and limited seating options in short actions. Eventually the .325 (8mm) WSM appeared. It offered a fine alternative to hunters wanting more bullet weight for elk, moose and big bears. Meanwhile, Winchester took short cartridges another step, with Super Short Magnums: .223, .243 and .25. The ballistic equal of much longer rounds, they did not feed smoothly. Hunters decided that there was nothing wrong with the .22-250, .243 Winchester or .25-06.

L-R: .340 Weatherby, .338 Winchester, 8.59 Lazzeroni Galaxy. The Galaxy out-performs the .338.

Prototype rifles in .300 RCM were synthetic-stocked Ruger 77 Mark IIs like this. They shot well!

Remington was late to the party with short magnums, though it could have announced the first of them soon after the WSM debut. It chose instead to promote its just-introduced line of Ultra Mags, the full-length 7mm, .300, .338 and .375. When the .300 and 7mm Short Action Ultra Mags arrived, Winchester had established its WSMs as the short magnums of record. In truth, Remington’s SAUM cartridges differ so little from their rivals that some chatter ensued on the possible hazards of switching ammunition. The Remington’s .300 is the better round, in my view. It’s very slightly shorter and, as slightly, more efficient. Also, it fits the compact Model Seven action, which does not as readily accept WSM rounds. I downed the first elk taken with the Remington .300 SAUM, using a Custom Shop Model Seven that’s still a favorite.

Remington’s R-15 rifle gave Wayne this group. The short .30 Remington AR cartridge is mild in recoil, deadly on deer.

Other short cartridges have followed the Winchester and Remington offerings, notably the .300 and .338 Ruger Compact Magnums, engineered by Hornady not only to deliver belted-magnum speed from short actions, but to outperform high-octane competition in short barrels. Mitch Mittelstaedt, who headed the project, explained to me that with new proprietary powders, his team was able to “tighten” pressure curves so the .300 RCM behaves like ordinary .30 magnums in 24 inch barrels but doesn’t lose as much enthusiasm in carbines. “Velocity of .300 WSM bullets drops 160 to 180 fps when barrels are chopped from 24 to 20 inches; RCMs lose 100.” With chronograph legend Ken Oehler, I chronographed .300 RCM loads from the 20 inch barrel of a Ruger carbine. The Oehler 35 gave me readings of around 2,840 fps with 180-grain bullets. Groups stayed around an inch. The accuracy was gratifying; short barrels are stiff.

L-R: .300 SAUM, .300 RCM, .300 WSM. They all outperform the longer and venerable .30-60.

Oehler sky-screens helped Wayne clock speeds from .300 RCM in a short-barreled Ruger rifle.

L-R: .300 WSM, .300 RCM, .300 SAUM. All wring .30-magnum speed from short actions.

Inspired by the 2.58 inch .375 Ruger, the .300 and .338 RCM share its .532 head and base. WSM rounds are bigger, with rebated .535 heads. RCM shoulder angles are 30 degrees. Case capacities average 68 and 72 grains of water to the mouth. For comparison, Remington .30-06 hulls hold 67 grains of water, Winchester .300 WSM cases 79 grains. Ruger Compact Magnums cycle through WSM magazines, but you can sneak four RCMs into most three-round WSM boxes. They’re loaded to the same overall length (2.84).

Long cartridges may be going the way of long automobiles. For riflemen keen to boost velocity without getting a haymaker punch to the chops, modern short magnums make sense!

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- CONTENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- SECTION I: BALLISTICS IN HISTORY

- SECTION II: THE MUSCLE BEHIND THE SHOT

- SECTION III: BULLETS—THE INSIDE STORY

- SECTION IV: SPEED, ENERGY, AND ARC

- SECTION V : PUTTING BALLISTICS TO WORK

- SECTION VI: FOR LONGER REACH

- BALLISTICS TABLES FOR MODERN SPORTING RIFLES

- GLOSSARY