8. Fuel for the Cartridge

From its inception in the fourteenth century until the middle of the nineteenth century, black powder generated the gas that pushed bullets out of gun barrels. Mild steels bottled its modest pressure. Nitroglycerine, discovered in 1846 by Ascanio Subrero in Italy, promised higher levels of performance at the expense of metal splitting pressure. “Nitro” is a colorless liquid comprising nitric and sulphuric acids plus glycerin. Unlike ordinary black powder, it’s not a blend of fuels and oxidants; it is instead an unstable, oxygen rich compound that can almost instantly rearrange itself into more stable gases. All it needs is a jolt. With age, nitroglycerine can become more unstable, more dangerous.

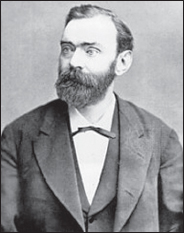

In 1863 Swedish chemist Emmanuel Nobel and his son Alfred figured out how to put this touchy substance in cans. That made it easier to handle but no less hazardous. Several shipments blew up. So did the Nobel factory in Germany. Alfred later discovered that soaking the porous earth Kieselguhr with nitro rendered the chemical less sensitive to shock. This process paved the way for dynamite, patented in 1875.

During the 1840s Swiss chemist Christian Schoenbein had found that cotton treated with nitric and sulfuric acids formed a compound that burned so fast the fire would consume the cotton without setting fire to a heap of black powder on top of it! Schoenbein obtained an English patent for his work then sold the procedure to Austria. Shortly, John Hall and Sons built a guncotton plant in Faversham, England. It blew up. So did most of the other guncotton plants built at the time. Chemists concluded this substance had little use as a propellant because it burned too fast and was too unstable. History had witnessed such problems with chlorate powders, pioneered by Berthollet in the 1780s. When a French powder plant at Essons blew up in 1788, potassium chlorate was deemed too sensitive for use in firearms.

Early rifle powders were all packed in metal cans. The first powder enterprises endured some horrific accidents. But manufacture of propellants in modern factories is much safer.

The mess attending black powder shooting led to the development of Pyrodex by Dan Pawlak. Hodgdon produces this black powder substitute, now available in convenient pellets as well as granules.

But eventually bright people figured out how to harness these frisky compounds. During the 1850s J. J. Pohl developed a fuel he called “white powder.” It comprised 49 percent potassium chlorate, 28 percent yellow potash, and 23 percent sulfur. Though a second-rate propellant, it served the Confederacy when during the Civil War black powder became unavailable. Wartime backyard powder mills turned out propellants of widely varying compositions and behaviors. Some performed well enough. Others proved useless or dangerous. Formulas were marketed through the mail by con artists who baited customers with claims that coffee, sugar, and alum, plus potassium chlorate, gave lethal thrust to any lead ball!

Keen to improve upon black powder and heartened by Nobel’s work with nitro, experimenters persevered. In 1869 German immigrant Carl Dittmar built a small plant to make “Dualin,” sawdust treated with nitroglycerin. In his native Prussia, he had run out of money trying to make smokeless powder from nitrated wood. But his efforts in New England showed promise. A year after completing the Dualin plant, he introduced his “New Sporting Powder.” By 1878 he was building a mill in Binghampton, New York. It blew up, taking part of Binghampton with it. When Dittmar’s health failed, he sold what was left of his firm. One of his foreman, Milton Lindsey, landed at the King Powder Company, where he worked with president G. M. Peters to develop “King’s Semi-Smokeless Powder.” They patented their formula in 1899. Dupont’s “Lesmoke,” which appeared soon thereafter, had roughly the same composition: 60 percent saltpeter, 20 percent wood cellulose, 12 percent charcoal, and 8 percent sulfur. One of several semi-smokeless powders of that time, Lesmoke proved a fine propellant for .22 rimfires. Fouling remained a problem but the residue didn’t harden as with black powder. Its soft residue gave semi-smokeless an advantage over the first smokeless powders, which left nothing to carry away residue from the corrosive primers of the day. Lesmoke was more hazardous to produce than smokeless, however. It was discontinued in 1947.

French engineer Paul Vielle is generally credited with the development of smokeless powder. In 1885 his “Poudre B” comprised ethyl alcohol and the ordinary proxylin known as celluloid. Poudre B is a single-base powder—no nitroglycerine.

French engineer Paul Vielle is generally credited with developing the first successful smokeless powder. His “Poudre B” comprised ethyl alcohol and celluloid. But in the 1870s, a decade before Vielle’s achievement, Austrian chemist Frederick Volkmann patented a cellulose-based powder. Unfortunately, Austrian patents were not acknowledged world wide and in 1875 Austria’s government began enforcing its monopoly on the domestic powder supply. Volkmann closed his plant then disappeared. His claims of transparent smoke, less barrel residue, more power, and safer handling would be borne out.

By 1887 Alfred Nobel had increased the proportion of nitrocellulose in blasting gelatin and found he could use the new compound as a propellant. A year later he introduced “Ballistite.” This double-base powder (it contained both nitrocellulose and nitroglycerin) was similar to a new powder developed at the same time by Hiram Maxim of machine gun fame. Concurrently, the British War Office started a search for a more effective rifle powder and came up with “Cordite.” With elements of both Nobel’s formula and Maxim’s, Cordite was named for a stage in its manufacture, when the propellant paste could be squeezed through a die to form spaghetti-like cords. The early formula included 58 percent nitroglycerine and 37 percent guncotton. These proportions were later changed to 30 percent nitroglycerine and 65 percent guncotton, plus mineral jelly and acetone. Nobel and Maxim sued the British government for patent infringement but got nowhere.

In 1863 Alfred Nobel, son of Swedish chemist Emmanuel Nobel, devised a way to put volatile nitroglycerine in cans. Later Alfred found that soaking porous earth with nitro stabilized the explosive. From this came dynamite, in 1875.

The .303 British, in the Short Magazine Lee Enfield, was one of the first military rounds fueled by smokeless powder, in the 1890s.

Nitrated lignin gave early smokeless powders a lumpy or fuzzy appearance. Variations in density posed problems for handloaders. “Bulk” powders could be substituted, bulk for bulk, for black powder. “Dense” or gelatin powders could not be safely measured by bulk, because their energy/volume ratios were higher. The shooting industry responded by marking shotgun loads in “drams equivalent.” In other words, the smokeless powder used gave the same performance as black-powder shotshells loaded with the marked number of drams. Handloaders charging rifle and pistol cases were advised to forget black-powder weights and treat smokeless as an entirely new fuel, with new rules.

L-R: The 6.5x55 is much older than (but not as potent as) the .260 Remington, 6.5 Creedmoor.

The 8mm Lebel, adopted by the French army in 1886, became the first military cartridge designed for smokeless powder. Other countries soon followed: England with the .303 British in 1888, Switzerland with the 7.5x55 Schmidt-Rubin in 1889. By the mid-1890s nearly all nations that could muster an army were equipping soldiers with small-bore bolt rifles firing smokeless cartridges. The new propellant boosted bullet speed by a third and didn’t give away a rifleman’s position with lingering clouds of spent saltpeter.

Oddly enough, most powder firms established in the 1890s failed. Fierce competition and flawed product, combined with the hazards of powder manufacture, made this a tough business. Many ambitious entrepreneurs who saw huge profit potential in smokeless propellant failed to secure government contracts, believing mistakenly that private sales could sustain a young company. As with rifles, one military contract could mean salvation. Rejection by Ordnance boded ill—even if, as one industry scribe claimed, American sportsmen burned “ … not less than three million pounds per annum.”

Mergers among powder companies were common. In 1890, Samuel Rodgers, an English physician living in San Francisco, formed the United States Powder Company to produce ammonium nitrate. Then he partnered with the Giant Powder Company to make “Gold Dust Powder,” comprising 55 percent ammonium picrate, 25 percent sodium or potassium nitrate, and 20 percent ammonium bichromate. The Giant Powder Company plant was destroyed by an explosion in 1898. At this time “Peyton Powder” by the California Powder Works was fueling .30-40 Krag ammunition for the US Army. Laflin & Rand manufactured its “W-A” double-base powder for the Krag (initials for developers Whistler and Aspinwall). “W-A” contained 30 percent nitroglycerin which contributed to its high burn temperatures and erosive tendencies.

Tennessee’s Leonard Powder Company marketed “Ruby N” and “Ruby J” powders until it folded in 1894. The American Smokeless Powder Company, a New Jersey firm, succeeded it, producing powder under contract for the government. Creditor Laflin & Rand acquired ASPC in 1898. Earlier, Laflin & Rand had sought American rights to Ballistite but considered Nobel’s price of $300,000 plus royalties too steep. Ballistite manufacture later came under the control of DuPont, which contracted that job to Laflin & Rand. “Lightning,” “Unique,” “Sharpshooter,” and “L&R Smokeless” powders originated at Laflin & Rand.

Alliant Powder (formerly Hercules Powder) offers eight ounce containers of its popular Reloder® series of smokeless powders for rifle reloaders. The product also is available in one pound and five pound offerings.

The Robin Hood Powder Company of Vermont became the Robin Hood Ammunition Company before it sold in 1915 to the Union Metallic Cartridge Company. The American E. C. & Schultz Powder Company was acquired by DuPont in 1903 then became part of Hercules when DuPont was split by court order in 1912. DuPont and the California Powder Works began filling military contracts in 1897 with nitrocellulose powders that resembled Cordite. Guncotton dissolved in ether and alcohol formed a colloid. Pressed into thin tubes, it was then chopped short. “Government Pyro” became one of the first of these powders to see military use, in the .30-06. DuPont later charged that cartridge with 1147 and 1185 powders. IMR (Improved Military Rifle) 4895 became the powder of choice for the .30-06 M2.

Wayne killed this Idaho elk with a Ruger rifle in 7mm Winchester Short Magnum, a cartridge made possible by high-energy propellants whose roots go back to the development of guncotton and nitroglycerin in the 19th century.

Even after Hercules started up its modern operation in Kenville, New Jersey, DuPont continued to dominate the market in small-arms powder. It manufactured up to a ton daily and produced large quantities of dynamite. By the onset of World War I, Hercules had established a factory in Parlin, New Jersey, there making nitrocellulose and popular rifle and pistol powders, including Bullseye, Infallible, and HiVel. But DuPont got the big war contracts. It established plants in Old Hickory, Tennessee, and Nitro (really), West Virginia. Combined capacity was 1.5 million pounds per day! After the war DuPont bought the town of Old Hickory to build a rayon factory. The powder magazines remained, however. One day in August, 1924, they caught fire. More than 100 buildings and 50 million pounds of powder vanished in a fearsome blaze.

High-velocity magnums get their sauce from progressive-burning powders that yield a sustained burn to accelerate long, heavy bullets without generating ruinous pressures. Shooters in the 19th century didn’t have them, didn’t need them.

During the Great War, Hercules manufactured Cordite powder for the British government—up to 12,000 pounds a day. Wartime Cordite production totaled 46 million pounds. In addition, Hercules sold 3 million pounds of small arms propellants and 54 million pounds of cannon powder. The conflict spurred companies like Hercules to improve powders and production processes. Plagued by copper residue fouling cannon bores, US munitions experts took a tip from the French and added tin to their propellants. Soon rifle powders got the same treatment. With 4 percent tin DuPont’s No. 17 became No. 17-½. No. 15 became No. 15-½. Tin levels were halved when dark rings appeared in the bores of National Match rifles, a result of tin cooling near the muzzle.

Hornady’s 6.5mm Creedmoor and the firm’s new Superperformance ammunition owe their success to powders that are far more efficient and temperature stable than early propellants, the manufacture of which destroyed many factories.

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- CONTENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- SECTION I: BALLISTICS IN HISTORY

- SECTION II: THE MUSCLE BEHIND THE SHOT

- SECTION III: BULLETS—THE INSIDE STORY

- SECTION IV: SPEED, ENERGY, AND ARC

- SECTION V : PUTTING BALLISTICS TO WORK

- SECTION VI: FOR LONGER REACH

- BALLISTICS TABLES FOR MODERN SPORTING RIFLES

- GLOSSARY