19. Headspace first

When you release the hammer or striker in your rifle, a lot of important events follow right away. The blow to the primer crushes its face against the anvil inside, smashing the shock-sensitive priming mix between them. The compound ignites—actually, it detonates. The explosion shoots flame through the flash-hole in the primer pocket. When this flame reaches the gunpowder in the case, the powder starts to burn, producing gas that expands rapidly. Because the brass case is ductile, it expands under gas pressure, ironing itself to the chamber walls. Still expanding rapidly, the gas thrusts the bullet forward, out the neck of the case and into the bore. At the same time, it pushes the case head against the bolt face. During this mayhem, the chamber keeps the cartridge in place. Because cartridges vary slightly in dimensions, and each must chamber easily, the chamber must be a little bit bigger than the average case.

Then there’s headspace, the distance from the face of the locked bolt to a datum line or shoulder in the chamber that arrests the forward movement of the cartridge.

“For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction.” So you’d expect the gas to press the cartridge head against the bolt-face. What complicates things is the taper of the case wall, from thick at the web to very thin at the shoulder. The web itself is a solid partition of brass around the flash-hole. As the front of the case is ironed against the chamber wall, the rear section stays close to its original diameter, slightly smaller than the chamber and, thus, mobile.

Now, if the case is held tight to the bolt face, everything is OK. The shoulder blows forward, the case body and neck outward to contact the chamber. The case head simply absorbs the rearward thrust of gas without moving because it is supported by the bolt face. But it’s unusual to have an unfired cartridge tight against the bolt face, because it would be very difficult to chamber—a press fit. A cartridge longer by a gnat’s lash would not chamber without great effort. So chambers are cut, and cases formed, to allow a bit of play. Call it tolerance. A proper chamber is slightly large, so the case head does move very slightly to the rear upon firing. If there’s too great a distance between the bolt face and the point in the chamber that stops the forward motion of a cartridge, however, you have a condition of excess headspace.

Understand that the striker’s blow pushes the cartridge forward until it contacts the datum point in the chamber. Expansion sticks it there because the thin front part of the case yields readily to gas pressure. The case head isn’t stuck because it is thick and doesn’t expand as much, so it moves rearward to meet the bolt face. The bolt face isn’t supporting the case head at this point, so the case stretches as gas pressure, leveraged against the bullet and the case shoulder, moves the head to the rear. The case wall just forward of the web can stretch a little without damage. But excess headspace may stretch it too far. Repeated firings “work harden” the case, reducing its ability to stretch. Given many repeated stretchings, a cartridge fired in a generous chamber can crack at the web, or even separate.

A cracked case is dangerous because it spills powder gas into the chamber. That gas seeks release, speeding down the tiniest corridors at velocities that can exceed bullet speed. It may jet along the bolt race, through the striker hole, into the magazine well. It can find your eye faster than you can blink….

Headspace is measured from the bolt-face to the mouth of a straight rimless case like the .45 ACP, whose mouth stops the case from going farther forward. In a belted magnum, the stop is the leading edge of the belt. On a .30-30 case it’s the front of the rim. The datum line for rimless or rebated bottleneck rounds like the .270 and .284 lies on the shoulder. Semi-rimmed cartridges theoretically headspace on the rim, but sometimes (as with the .38 Super Automatic) the rim protrusion is insufficient given the action tolerances needed for sure function. The case mouth then serves as a secondary stop. The semi-rimmed .220 Swift has a more substantial lip; but most handloaders prefer to neck-size only, so after a first firing, the case actually headspaces on the shoulder. More on that later. The term “headspace” originated when all cartridges had rims, so the measurement was initially made only at the head. Now rimless and belted rounds are the rule. Headspace as a dimension includes all measures of bolt-face-to-cartridge stop.

Gunsmiths measure headspace with “go” and “no go” gauges. The “go” gauge is typically .004 to .006 shorter than the “no go” gauge for rimless and belted cartridges. The bolt should close on a “go” gauge but not on a “no go” gauge. Theoretically, if the bolt closes on a “no go” gauge, the barrel should be set back a thread and rechambered to achieve proper headspace. However, many chambers that accept “no go” gauges are still safe to shoot. The “field” gauge, seldom seen now, has been used to check these (mostly military) chambers. It’s roughly .002 longer than a “no go” gauge.

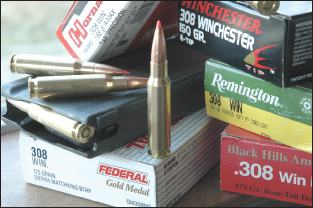

The wide variety of factory loads now available drains handloads of some of their exclusivity.

Minimum and maximum headspace measurements are not the same as corresponding minimum and maximum case dimensions. For example, a .30-06 chamber should measure between 1.940 and 1.946, bolt face to shoulder datum line. A .30-06 cartridge usually falls between 1.934 and 1.940. Case gauges machined to close tolerances perform the same check on cartridges that headspace gauges do in chambers. An obvious difference: Case gauges are female and cannot accurately gauge headspace. They simply show whether a cartridge will work in a chamber that’s correctly bored and fitted. Headspace is a steel-to-steel measure in the gun. Altering case dimensions does change the relationship of cartridge to chamber. And reducing the head-to-datum line length of a hull can result in a condition of excess headspace, even if the firearm checks out perfectly.

Once I was sizing cases for a wildcat 6mm cartridge, the .240 Hawk. The custom sizing die had been made to reduce the neck diameter of the .30-06 case without changing the shoulder or datum line. I set up the die initially to full-length resize, so I’d be starting with cartridges that would easily fit the chamber. After one firing, I would neck-size only to get a tighter fit and prolong case life.

My first shot blew gas from all the crevices of the stout Remington 700 action. The case showed a circumferential crack forward of the belt. Because the loads were not stiff, and because the bolt lift did not indicate high pressure, I fired another round. Same result. At the bench, I compared the sized cases with the fired cases. The sized .240 hulls were shorter by nearly .1 inch. I screwed the die into the press but left it 1/8 inch short of contacting the shell-holder. I ran a case into the die, then tried chambering it in the rifle. It wouldn’t go. I ran the die down a thread and sized the case again. No go. Lowering the die incrementally and trying the case each time, I finally closed the bolt. It was a snug fit. I looked at the relationship of die and shell-holder. There was a gap of .1 inch—the measure of the difference between fired and unfired cases. Unlike most commercial dies, this one had not been machined to full-length size when flush with the shell-holder. Screwing it down that far, I had made the case .1 shorter than the rifle’s chamber. When I fired, the striker drove the case forward .1 inch. The front of the case expanded into the chamber to grip it, and the rear of the case backed up .1 inch against the bolt, pulling the brass apart just ahead of the web.

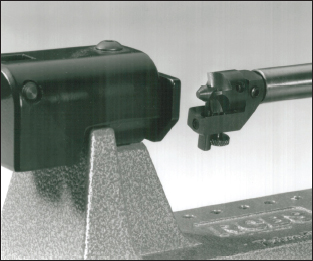

Pressure spikes can result from an over-length case, when the case-mouth is pinched in the chamber. Case trimming to proper length ensures clean bullet release. This RCBS trimmer makes the job easy.

If headspace can legitimately vary .006, and the corresponding case dimension another .006, it’s possible to load a round .012 shorter than the chamber will allow, bolt face to stop. Full-length sizing dies, when set so the shell-holder presses tight at the end of the stroke, should not bring cases below minimum.

Even if rifles and cartridges could be manufactured to zero tolerances, you wouldn’t want zero-tolerance chambering in a hunting rifle. The least bit of dust, water, snow or residual oil might prevent easy bolt closure and a missed opportunity. Changes in temperature can also affect cartridge fit. In a revolver, the breech face cannot have contact with the case head without risk of tying up the cylinder. Snug fit of straight cases in autoloading pistols means that any jump at all in case length keeps the slide out of battery.

Full-length resizing compresses a cartridge case; firing stretches it. Think for a second about what happens after the repeated bending of the tab on a can of soda pop. To prolong case life, you’re better off to neck-size only, so the brass moves little upon firing. Because a cooling hull shrinks after firing (otherwise you couldn’t easily extract it), there’s no need to further reduce its dimensions unless you plan to use the ammunition in another rifle that has a slightly smaller chamber. The only other reason to full-length size (or to use small-base dies that squeeze cases down even further) is to accommodate autoloading or lever- or slide-action rifles that have little cramming power. Some hunters full-length size the cases they’ll use on a hunt, to ensure easy chambering in the event they must fire quick follow-up shots.

Weatherby’s Mark V action, announced 1957, accommodates huge cartridges like the .378, .460.

Neck sizing is a particularly good practice with belted cases, because chambers for these hulls are often cut generously up front. The critical dimension, after all, is the distance from bolt face to belt face (.220 to .224, “go” to “no go”). If you full-length-size belted magnums, you may be shortening the head-to-shoulder span considerably each time—which means the case stretches a lot at each firing. Eventually (sometimes quite soon), you’ll notice a white ring forming around the case just ahead of the belt. If you insert a straightened paper clip with a small “L” bend at the end and feel around the inside of the case, you may detect a slight indentation forward of the web. The white ring signals a thinning of the case and shows where the case will separate if you keep full-length sizing the case.

Rechambering rifles to Improved, or sharp-shouldered, cartridges should not change headspace measurement. The reduced body taper and steeper shoulder angle provide greater case capacity, but the datum point on an altered shoulder should remain the original distance from the bolt face. That’s why you can fire factory ammunition in an Improved chamber safely. True wildcats that require case forming in dies must sometimes be given a false shoulder to serve as the chamber stop before firing full-power loads. For example, the Gibbs wildcats pioneered in Idaho by Rocky Gibbs in the 1950s, and the more recent Hawk cartridges, are based on the .30-06 with the shoulder moved forward. To fashion the .338 Hawk case, you might neck a .30-06 up to .375, then neck that hull down to .338 in a Hawk die. The result would be a case with two shoulders. The rear one would disappear upon firing. An alternative method would be to neck the .30-06 to .338, then seat a bullet to contact the lands as the bolt is closed. Hard against the lands, the bullet keeps the head of the case tight to the bolt face. Use a reduced powder charge. Handloaders who make false shoulders commonly employ small doses of fast powder behind a case filler of corn meal, with a wax cap.

Few hunters think about headspace. But the shot that gave Dori Riggs this fine Namibian warthog depended on proper fit of the cartridge in the chamber.

Often shooters who don’t understand headspace blame it for all sorts of problems not related to headspace. The first centerfire rifle I owned was a surplus Short Magazine Lee Enfield. The rimmed .303 British cartridges fed like Vaselined sausages, but roughly one in four separated upon firing. Now, several things could have been wrong. Because headspacing on SMLE rifles can be changed merely by switching bolt heads, the bolt itself was even suspect. The cases in this instance were of new commercial brass, so my ammunition escaped scrutiny.

Kimber’s long-action 84L is one of the sleekest .30-06 sporters around, and, at 6 pounds, accurate.

I didn’t know enough about rifles then to figure out what was wrong, but I did know that repeat shots at whitetails were improbable if I had to wait for the barrel to cool and use a rod with a tight brush to extract the fronts of broken cases. I was loath to part with the rifle, because I’d worked hard for the $15 it cost. My elders, mostly farmers with 97 Winchester pump guns and Krags as old as my .303, didn’t know what to tell me. In desperation I took it to an ill-tempered gun-smith, who peered into the breech, examined one of my two-piece cases and declared that I had a “swelled chamber.” I didn’t know how chambers could swell, but he convinced me to sell him the rifle. My second SMLE cost twice as much, and I slapped down an additional $7.50 for a Herter’s walnut stock blank that took weeks to fit. Somewhere I found $10 for a set of Williams sights. The cases all extracted, though, and some deer bit the dust.

Rimmed rifle cases (right) headspace on the rim. Rimless rounds headspace on the shoulder (straight rimless pistol cartridges on the case mouth).

L-R: .458, .338, .264 Winchester Magnums, 7mm Remington Magnum, introduced 1956-1962.

Some years later I spied queer marks on hulls kicked out of an M70 Winchester in .338 Magnum. They were white lines, but not in the usual place. Inspection of the chamber revealed an old gas cut. So I threaded the flash-hole of a fired .338 case and screwed in a ¼ inch rod. Then I chucked the rod in a variable-speed drill and secured the rifle in a vise. After smearing the case body (but not the belt!) with J-B’s abrasive paste, I carefully fed the case into the chamber. The drill, turning slowly, polished the chamber without removing so much metal as to materially change its dimensions. It smoothed the edges of the gas cut and reduced its depth. The marks on fired cases all but vanished.

Headspace is a length measurement. It has nothing to do with diameter. Chambers that are egg-shaped or belled by unprincipled cleaning, or whose diameters are larger or smaller than normal may cause problems, but they’re not headspace problems. Headspace hinges on reamer dimensions as well as on the machinist’s eye and expertise. After long use, reamers cut slightly smaller chambers than when new. New reamers or those used aggressively can bore oversize chambers.

Headspace can change over time. With each firing of your centerfire rifle, some compression of the locking lugs and lug seats occurs. The elasticity of the steel keeps headspace essentially the same. But many firings with heavy loads can drain that elasticity and cause a permanent increase in headspace. A rifle with hard lugs and soft seats and generous headspace can eventually develop so much headspace that a field gauge can be chambered. At this point the rifle is unsafe.

Headspace is a chronic problem with early lever-action rifles built for rimmed rounds. Shooters seldom fret about it, partly because these cartridges, some originally loaded with black powder, develop relatively low pressures. Riflemen who handload for old lever guns wisely keep charges mild. Loose, rear-locking actions are intrinsically difficult to hold to the tolerances of front-locking bolt rifles. Handloaders with ailing saddle guns can keep them in service and prolong case life by peening the rims of cases before firing. Careful peening from the side, with frequent testing in the action, boosts rim thickness to match the chamber cut. Tedious but effective.

There’s nothing mysterious about headspace. It’s simply a measurement between the bolt-face and the place in the chamber that stops a cartridge from moving farther forward.

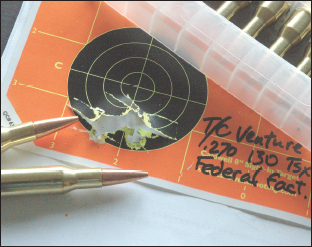

With Federal-loaded 130-grain TSXs, the inexpensive T/C Venture shoots beyond its price.

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- CONTENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- SECTION I: BALLISTICS IN HISTORY

- SECTION II: THE MUSCLE BEHIND THE SHOT

- SECTION III: BULLETS—THE INSIDE STORY

- SECTION IV: SPEED, ENERGY, AND ARC

- SECTION V : PUTTING BALLISTICS TO WORK

- SECTION VI: FOR LONGER REACH

- BALLISTICS TABLES FOR MODERN SPORTING RIFLES

- GLOSSARY