32. Notes on handloading

Last month I visited Cooper’s Landing, Alaska half a century ago. Well, not really. I was at the loading bench concocting loads for the .450 Alaskan. This wildcat cartridge, attributed to Harold Johnson, who plied his trade as a gunsmith in the post-war Far North, is a powerful round that hurls 400-grain bullets at 2,150 fps. It beats the British .450/400 that in another day seemed a match for Bengal tigers and even big African game. Handloading the .450 Alaskan took me to Alaska’s frontier when the state was still new. Hardy men in woolens and shin-high leather boots probed alder jungles for brown bears and threaded willow thickets for moose.

Among the most revered rifles for such duty was Winchester’s Model 71, descendant of John Browning’s powerful, elegant Model 1886, the first successful vertical-lug lever rifle. The 71 chambered a new cartridge, the rimmed .348 Winchester. The 250-grain bullet at 2,350 fps churned up 3,000 ft-lbs—as much as a .30-06. But the blunt noses required of bullets in the 71’s tube magazine limited reach. By the rifle’s 1935 debut, hunters were lusting after scoped bolt rifles launching rocket-shaped bullets. The 71 didn’t last long; production ended in 1957.

“See what you can do with it.” Steve Kerby had loaned me his converted 71, with a batch of expanded .348 cases, months earlier. Other projects got in the way. At last I shut the door to the twenty-first century and pawed through my stash of powders. I picked Scot 3032, H322, H4895 and Winchester 748, with bullets from Northern Precision and Hornady and Speer, 325 to 400 grains.

Wayne used handloads in this high-performance 6.5 by Greybull to shoot a gong at a range of one mile.

Wayne’s handloads for the .250 Savage produced this group. Handloading can make old rounds shine.

Expanding a .348 case to 45-caliber is best done in two steps. RCBS forming dies with .30-to-.40 then .40-to-.45 expander balls yield a straight, tapered case. Firing a loaded round in a .450 Alaskan chamber puts a shoulder into the hull and reduces body taper. I hand-weighed charges of powder and seated bullets without crimping. Had these been hunting loads, I would have crimped the bullets in place, because the stiff recoil of the .450 Alaskan can overcome neck tension and jam bullets back in their cases in the magazine. To form cases, I’d load singly.

Boom! Even without game in the sights, shooting the 71 and home-brewed loads was great fun. The cases emerged beautifully formed, with no pressure signs— though one charge drove 400-grain Speers at nearly 2,100 fps.

For years, the .22-250 was a wildcat. Shooters had to load their own ammunition. Then Remington adopted the popular varminter.

You don’t have to fashion wildcat cartridges to get something out of handloading. Stoking your own .270 with cartridges you assembled yourself is like tying your own flies or making your own arrows. Handloading gives you a bigger role in the shot, more investment in a trophy. If you shoot as much as necessary to shoot confidently, rolling your own will save you money.

Redding dies and Norma brass and Accurate 3100 powder: recipe for a potent load. Bullet? Your choice!

When I first considered handloading, I wondered if the investment in tools would ever be erased by savings in ammunition. After all, a Herter’s press cost $15, and I’d pay that much more for a powder scale. I’d need dies too, at $10 per set. Components—bullets, cases, powder and primers—hiked the tab. With factory-loaded .303 softpoints at $5 a box, I almost demurred.

Having since saved enough money handloading to buy a well-equipped sedan, I find that earlier reasoning absurd. But many hunters still hesitate. If you shoot only a box of ammo each year, any savings will take a long time to appear. On the other hand, if you’re not shooting more than that, you’re not getting much practice as a marksman.

Another traditional reason to handload was to improve rifle performance. Handloaders enjoyed more bullet options and could tweak components and velocities to improve ballistic performance and accuracy. These days, that rationale carries less weight. The best of current factory loads are good indeed. Bullet choices rival those available to handloaders, because ammo firms are partnering with bullet makers to load bullets once sold only as components. Still, you have many more options as a handloader. Powders have proliferated too. “We carry 120 kinds, including Winchester and IMR powders,” says J.B. Hodgdon. “That’s 70 percent of the market.” Incidentally, Bruce Hodgdon started his business 60 years ago with just one powder: war-surplus H4895. Next came H4831, a 20mm cannon powder available in huge quantities after the war. During my college days, I bought a 50-lb keg for $150. With barely enough cash left for primers, bullets, tomato soup and the month’s rent, I plunged into handloading. In my .270, a 130-grain Sierra and 59 grains H4831 sent mule deer head over heels. I killed my first elk with a 180-grain Speer atop 69 grains H4831 in a .300 H&H. Today H4831 remains a top choice for magnum hulls. The Short Cut version sifts easier. (Note: Slow powders like H4831 should not be used in reduced charges. Detonation can occur, perhaps due to colliding pressure waves when primer flame spans the half-charge to start a secondary burn.)

At the moment of truth, we depend on one cartridge. Handloads can be as reliable as factory ammo.

Another fine traditional powder is H4350. Slightly faster than H4831, it’s perfect for heavy-bullet loads in the .30-06, and for middle-weight bullets in medium-bore magnums. There’s no better powder in the .257 Roberts or .280 Remington. My .25 Souper (a neckedup .243) uses 46 grains H4350 to launch 100-grain Speers at 3,240 fps. With 55 grains I get 3,010 from 140 Nosler Ballistic Tips in my .270s.

Versatility is the hallmark of H4895. Mid-range on burning-rate charts, it excels in the .308 and .30-06, and accommodates a wide range of bullets in most mid-capacity cases. It excels in big-bore rounds like the .375 H&H, yet remains a favorite in the .223. In a .338-06, 57 grains milks 2,850 fps from 200-grain Hornadys; 49 grains drives 180-grain Nosler Ballistic Tips at 2,800 from the .338 Federal.

Some new factory ammo—here Hornady’s for the .300 RCM—is hard to match at the loading bench.

Practical pressure ceilings limit how far you can hike performance. When handloading cartridges like the 6.5x55 and .45-70, developed in rifles more than a century old, you can easily beat chart velocities. Modern actions and barrels permit friskier loads than would be safe in original rifles, whose presence dictates that ammunition firms observe conservative pressure lids. But high-octane cartridges, like Norma-loaded Weatherby Magnums and short magnums introduced during the last decade, may be up against the throttle peg from the start. Matching velocities of Hornady Superformance or Federal High Energy ammo can push pressures to case-sticking levels. That’s because we handloaders lack access to some powders and loading techniques that make such hot-rod factory loads possible.

You’ll still benefit from handloads with components matched and assembled to deliver the best accuracy in your rifle. You can tune loads to make certain bullets shoot faster or more accurately. To learn techniques that yield the best results quickly, consult manuals from Barnes, Hornady, Norma, Nosler, Sierra, Speer, Swift and Vihtavuori. Handloading is mostly science, and technique matters. Here are a few tips for better handloads—and caveats that might prevent wasted hulls, malfunctions, a wrecked rifle or a face-lift.

Accuracy like this, plus sizzling velocity, now comes in factory ammo. Hard to beat with handloads!

Try as many combinations of bullets and powders as you can, after comparing at least three manual listings for the cartridge. Why three? Test procedures and rifles vary; so may barrel lengths used to develop velocity tables. Reconcile differences between manuals; pick powders that generate the highest velocities in all three. Pay attention to case volume; slow powders that deliver acceptable speed may require such high charges weights that you run out of powder space. Getting all the powder you can into a case is best done with a drop tube, and by tapping the base of the case as you rotate it on its rim. Crushing powder by seating the bullet should have no effect on accuracy, velocity or safety. But compressed charges are slow to load. Ball powders don’t compress as well as stick powders, and you may find bullets creeping out of severely compressed loads. My rule of thumb: Keep powder levels at mid-neck—the base of the neck for ball powders. If you need more fuel than that to reach target velocities, try a faster powder.

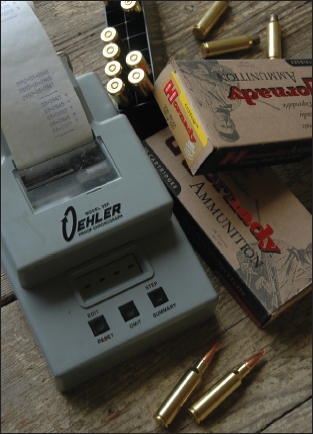

To make your dollar go farther when trying new powders, split canisters with friends. Ditto for boxes of bullets. Load three, four or five cartridges at a time. Chronograph them. After you whittle your options, assemble 10 or 12 cartridges at a time and shoot enough groups to find the most accurate. Then buy components in quantity.

“The Tube” was developed by Richard Mann, who wanted a convenient way to assess a bullet’s terminal performance. A softpoint from a small-caliber rifle plowed this channel.

You’ll lubricate cases before sizing. A light coating is enough—too much lube will dent the case shoulder. Don’t forget the inside of the neck. Use dry lube on a brush, or press the case mouth into a pad soaked in liquid lube to put a bead on the rim. The expander ball will have an easier job, and it won’t tug the neck on exit.

Neck-size if loading for one rifle. Full-length sizing unnecessarily works brass, reducing case life. Belted cases, full-length-sized and fired in generous chambers, can fail quickly just ahead of the belt. You’ll see damage there as a light-colored ring that portends case separation. A thin dark line in this pale belt is a crack waiting to spill gas. Discard that case, and examine carefully other cases from that lot. Gas loosed in the chamber can find its way back through the bolt. If the case head separates, you may need a tool to remove the front—which you won’t have when an elk is staring you down in the lodgepoles. Gas also cuts chambers like a blow-torch. Once you’ve fired a belted case, baby it by setting your die a dime’s thickness above the shell-holder. The sized case should fit nicely in the chamber it came from, and will grip a bullet securely. When loading a round for different rifles or to ensure easy chambering, size the shoulder only as much as necessary. (Shabbily-cut chambers that are out of round may resist neck-sized rounds oriented differently than when they were first fired; but this is a rifle problem, and one to correct.)

Don’t test pressure limits. Sticky extraction, flattened primers and shiny ejector marks on case heads warn of pressures that impair accuracy and rifle function and reduce case life. By the time extraction becomes difficult, pressures are already beyond reasonable. Back off! Measuring case head expansion helps you keep tabs on pressure.

Keep cases trimmed to recommended length. A long case may not chamber. If the case mouth contacts the end of the chamber and you manage to close the bolt, the mouth will collapse into the bullet, effectively crimping it. But unlike a deliberate crimp, which releases after ignition as the neck expands to release the bullet, a case mouth up against the chamber end has no place to go. Its compression of the bullet greatly increases drag. Pressures can spike.

There’s nothing wrong with trimming rifle cases a tad short. That way you can get several firings before having to trim again. (Avoid this practice when trimming cases that headspace on the mouth—like the .45 ACP.) Be sure to de-burr case mouths inside and out after trimming, for easy bullet seating and sure function in the rifle. If you crimp, set the die to deliver no more mouth compression than you need. Crimp only on a crimping groove or a cannelure.

When not crimping, you’re free to seat bullets farther out than the cannelure indicates—within the limits imposed by your magazine and throat. Cartridges must fit comfortably in your magazine, and when you chamber one, the bullet’s shank must lie shy of the rifling. Seating a bullet so far out that the rifling grips the bullet can be bad news. Not only does the contact deprive the bullet of an easy release; if the rifling engraves far enough onto the shank, it can win in a tug of war when you try to extract the loaded round. That is, you’ll pull the case off the bullet, spilling powder into your magazine and leaving the bullet stuck in the bore. I like to seat bullets to within about .1 inch of the rifling. Accuracy can suffer if the bullet must make a long leap. To check throat length, seat a series of bullets progressively farther out until you feel one contact the rifling. Check for rifling marks (smoking a bullet with a match before chambering, you’ll see them more clearly). Then set your seating die at least .1 deeper.

Load all handloads into your rifle’s magazine and cycle them before you hunt or enter a match!

When finished, label all handloads immediately. You will not remember powder charges tomorrow!

Run all handloads through your rifle, from the bottom of the magazine up, to ensure function. You want to know they’ll feed now, before you cycle the bolt on an irate leopard or a spruce-bound Boone and Crockett moose.

Faultless feeding is a requisite in hunting rifles. This Blaser R93 slicks up well-assembled .375 handloads.

At the range, as at the bench, mind what you’re doing. Handloading requires only ordinary intelligence but extraordinary vigilance.

Once, on the range with a fellow who’d bought a lovely .270 from me, I heard a loud report. A quavering call for help brought me running. My amigo was bleeding around his shooting glasses, but didn’t seem badly hurt. His rifle, though, was in shambles, its French walnut stock split in three pieces, the extractor gone, the bolt frozen. “Those handloads of yours…” He winced as he wiped his brow. I examined the box of .270s. I’d loaded them with H4831. It’s nigh impossible to get enough H4831 in a .270 case to blow up a 98 Mauser. In fact, I was sure I could card off a charge and seat a 130-grain bullet without exceeding safe pressures. The box in my hand wore my label, in my writing. H4831. The only thing wrong, I noticed suddenly, was that the box was full. I pointed this out, asking where the delinquent round had come from. Dave picked up another box. I saw instantly that it held .308 cartridges—suitable for the other rifle he owned. In haste he’d grabbed that ammo by mistake. Chambered in a .270, a .308 is poison. The shorter case slides right in. But squeezing a .308 bullet through that .277 bore, the rifle became a bomb.

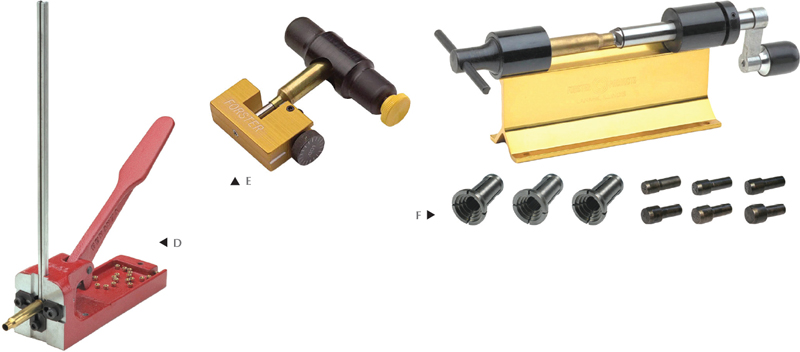

Tools of the Trade: a Forster 3-in-1 on base with cases (A); Forster bench rest sizing and seater dies (B); Forster co-ax press (C); Forster co-ax press primer seater (D); Forster hand-held outside neck turner (E); and Forster case trimmer kit (F).

More recently, on the bench with a borrowed lever rifle, I thumbed back the hammer and squeezed. Clack. I held the rifle securely for several seconds, in case of a hang-fire. When I opened the action, an empty case tumbled out. First thing to mind: “I forgot to cycle.” But it’s always wise to consider every possibility. Action open, I looked into the muzzle. Dark. The wildcat cartridge I’d chambered had been taken apart by the rifle’s owner, formed, then reloaded with the original powder charge and bullet. Except he had forgotten to include the powder. When I pulled the trigger, the primer blast pushed the bullet into the throat. The primer’s report couldn’t escape from case or bore; it was further muffled by the hammer fall. Had I levered in a live round and fired it, the results would have been jarring. Expanding gas would have had to shove two 200-grain bullets down the bore. To make matters infinitely worse, the front bullet would have interrupted the forward travel of the one behind just as gas pressure was peaking!

Handloading is great fun. It can bring you to a different place and time, wring more accuracy and possibly even more power from your rifle. It becomes a personal investment in your hunt, your own signature at its climax.

Handloading treats most kindly riflemen who mind what they’re doing.

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- CONTENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- SECTION I: BALLISTICS IN HISTORY

- SECTION II: THE MUSCLE BEHIND THE SHOT

- SECTION III: BULLETS—THE INSIDE STORY

- SECTION IV: SPEED, ENERGY, AND ARC

- SECTION V : PUTTING BALLISTICS TO WORK

- SECTION VI: FOR LONGER REACH

- BALLISTICS TABLES FOR MODERN SPORTING RIFLES

- GLOSSARY