7. Primers: Sparkplugs with Bang!

Centerfire rifle primers hail from the percussion cap of the mid-nineteenth century. Drawn brass, solid head cartridge cases have no anvil, so beginning in 1880, primer cups have been manufactured with anvils. Installed in cases with a central flash hole, they’re called Boxer style primers. They come in two sizes for rifle cartridges, two for handguns.

Large and small rifle primers are of the same diameter as large and small pistol primers respectively, but the pellets inside differ. You need more spark to ignite heavy charges of slow rifle powders. The spark of magnum primers lasts longer than that of standard primers. By the way, a large rifle primer weighs about 5.4 grains and carries .6-grain of priming compound.

Early on, European cartridge designers followed their own path, incorporating the anvil in the case and punching two flash holes in the primer pocket on either side of the anvil, which is part of the case. This Berdan design has a couple of advantages over the Boxer: there’s more room in it for priming compound and the flame can go straight through the holes rather than having to scoot around the anvil and its braces. The Boxer primer owes its popularity largely to hand-loaders, who can pop the old primer out while sizing the case in a die with a decapping pin. Berdan primers must be pried out with a special hook or forced free with hydraulic pressure. Oddly, Edward Boxer, for whom American style primers are named, was British. Europeans named their primer after Hyram Berdan, an American. Both men were military officers.

Early Boxer primers ignited black powder easily but sometimes failed to fire smokeless. When more fulminate was added to the priming mix, cases began to crack. Blame fell on the propellant, but the culprit was really mercury residue from the primer. Absorbed by black powder left in the cases, mercury accumulated to attack the zinc in case walls, causing them to split. A typical primer at this time contained 41 percent potassium chlorate, 33 percent antimony sulfide, 14 percent mercury fulminate, and 11 percent powdered glass.

Centerfire rifle primers feature an anvil, here a tripod-shaped fixture. The hardened mix of explosives beneath is ignited by the striker’s blow, which crushes it against the anvil.

A centerfire cartridge (left) holds a self-contained primer, with anvil and explosive. In a rimfire case, the priming mix is deposited inside the rim. The chamber lip serves as the anvil for the striker.

The first successful non-mercuric primer for smokeless loads was the military H-48, developed in 1898 for the .30-40 Krag. Its primary detonating component was potassium chlorate, whose corrosive salts did not damage the case. It could wreak havoc with bores, however, by attracting water and causing rust. Cleaning with hot water and ammonia, followed by oiling, was required after shooting to keep rifling shiny.

In 1901 the German Company Rheinische-Westphalische Sprengstoff (RWS) introduced a primer with barium nitrate and picric acid instead of potassium chlorate. These compounds did not cause rust. Ten years later the Swiss had a non-corrosive primer and German rimfire ammunition featured Rostfrei (rust-free) priming. Rostfrei contained neither potassium chlorate nor ground glass, an element commonly used in other primers to generate friction when the striker hit. Unfortunately, this otherwise ideal sparkplug left a residue of barium oxide, which could scour a barrel as aggressively as did glass. American military primers were glass-free before World War I when the FH-42 supplanted the H-48.

Primer production during the Great War overloaded drying houses Stateside, causing sulfuric acid to build up in priming mix. Misfires resulted. The FH-42 was replaced by the Winchester 35-NF primer, later known as the FA-70. This corrosive primer contained 53percent potassium chlorate, 25 percent lead thiocyanate, 17 percent antimony sulfide, and 5 percent TNT. It remained in military service through World War II.

The .22 rimfire cartridge dates to the 1850s and work by Horace Smith and Dan Wesson. Note the striker mark on the rim of this fired .22 cartridge.

Remington was the first US firm to announce non-corrosive priming in sporting ammo under the “Kleanbore” label in 1927. Winchester followed with “Staynless,” Peters with “Rustless.” All contained mercury fulminate. German chemists Rathburg and Von Hersz later managed to remove both potassium chlorate and mercury fulminate from primers. Again Remington took the lead with the first US version of a non-corrosive, non-mercuric primer. The main ingredient (then comprising up to 45 percent of the mix) was lead tri-nitro-resorcinate, or lead styphnate. It remains an important component in small arms primers. The US Army adopted non-corrosive, non-mercuric primers in 1948 and currently uses one designated FA-956. It comprises 37 percent lead styphnate, 32 percent barium nitrate, 15 percent antimony sulfide, 7 percent aluminum, 5 percent PETN, and 4 percent tetracene.

During the 1940s, development of big, broad-shouldered rounds and extra-slow-burning powders called for a stronger ignition flame. More priming compound was not the answer, because it might shatter powder directly in front of the flash hole, causing erratic pressures and performance. Dick Speer and Victor Jasaitis, a chemist from Speer Cartridge Works, came up with a better idea, adding boron and aluminum to the lead styphnate to make the primer burn longer. The result would be more heat and more complete ignition before primer fade. Other munitions companies latched onto this development. Speer primers, still made in Lewiston, Idaho, wear a different label these days: CCI (Cascade Cartridge Industries).

The same primer problems were visited on shotshell production—which found its salvation in the same quarters. But shotshell cup assemblies differ from rifle primers. A deep battery cup holds the anvil and a smaller cup containing the detonating material, protected by a foil cover. A shotshell’s primer pocket has no bottom, hence, no flash hole. The flash hole is in the battery cup. Made of thin, folded brass like old balloon-head rifle cases, shotshell heads are reinforced with a dense paper base wad or a thick section of hull plastic. Battery cups seal the deep hole in the base wad.

While the machines that produce primers are more sophisticated now, primer manufacture is much the same as it was at the outbreak of the second world war. Huge batches of primer cups are still punched and drawn from sheet metal and indexed on large perforated metal tables. Perforated plates are smeared with wet priming compound the consistency of fresh dough and laid precisely on top of the tables so the dabs in the holes can be punched down into open faced cups. Or the cups are filled by workers brushing the compound across the face of the table. Next comes the thin foil disc (or a shellacked paper cover). Anvils, punched from another metal sheet, are inserted as the plates line up. Priming mix is stable when it is wet, but extremely hazardous to work with when dry. No mix is ever allowed to dry in the primer room.

Winchester’s Model 70, now in production again, has been chambered from .22 Hornet to .458.

Primer choice can influence pressures, velocity, and accuracy; however, most modern primers are both reliable and uniform in their ignition characteristics.

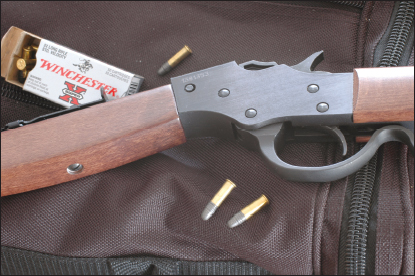

This modern rendition of the Stevens Favorite, a popular single-shot .22, has an exposed-hammer, dropping-block action with offset striker to hit the cartridge rim, where the priming mixture resides.

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- CONTENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- SECTION I: BALLISTICS IN HISTORY

- SECTION II: THE MUSCLE BEHIND THE SHOT

- SECTION III: BULLETS—THE INSIDE STORY

- SECTION IV: SPEED, ENERGY, AND ARC

- SECTION V : PUTTING BALLISTICS TO WORK

- SECTION VI: FOR LONGER REACH

- BALLISTICS TABLES FOR MODERN SPORTING RIFLES

- GLOSSARY