17. Speer, Nosler, Hornady

Vernon Speer was born in 1901 in Cedar Falls, Iowa. After a stint in the US Navy during World War I, he indulged an interest in aviation by building his own aircraft engine at age 21. He then installed it in a biplane and took to the sky in a test flight. Work as a tool foreman for John Deere grounded him for a while, but in 1941 he became chief ground instructor at a flying school in Lincoln, Nebraska. There he also started making bullets. Handloading was in its infancy; shooters still cast their own bullets. Jacketed bullets hadn’t yet become widely available, and the war effort caused shortages in both brass and copper. Vernon Speer struck upon the idea of using .22 rimfire cases for bullet jackets. He built a machine to iron out the rims and draw the hulls to proper dimensions for .224 jackets. His partnership with Joyce Hornady proved as fragile as most, and in 1944 Speer left Hornady and Nebraska to establish his own business in Lewiston, Idaho. For two years he sold his jacketed .224 bullets in paper bags, while laying the groundwork for a new bullet manufacturing plant on the banks of the Snake River. That’s still where Speer bullets come from.

War’s end renewed the flow of gilding metal to the commercial ammunition industry. Speer took advantage by expanding his line of bullets to include all popular types and diameters. His son Ray joined the growing company in 1952. Two years later Ray produced the first Speer Reloading Manual. Ever the experimenter, Vernon Speer developed the Hot-Cor process to ensure better marriage of the bullet core and jacket. He realized early on the advantages of reusable packaging and bought injection molding equipment to make sturdy plastic boxes for Speer products. In 1969 he began loading his bullets in handgun cartridges, introducing the Lawman line of ammo. Gold Dot bonded pistol bullets came along in 1994. They and the subsequent Gold Dot ammunition have earned enviable reputations among law enforcement officers. Speer remained a family-owned business until 1975, four years before Vernon Speer’s death.

While Vernon’s name is widely known among shooters, his brother Dick also contributed a great deal to the growth of handloading. Fourteen years younger than Vernon, he became a machinist at Boeing Aircraft in Seattle. After Speer’s bullet factory began operation in Lewiston, Dick moved there to produce specialty cartridge cases. Shooters keen to brew handloads for discontinued, proprietary, or wildcat rounds took note. First selling the hulls under the label “Forged From Solid,” Dick named his part of the business Speer Cartridge Works. While his extrusion processes were sound, the quality of raw stock varied widely in those days. Consequently, so did case quality. A high rejection rate, combined with the limited market in specialty brass, scuttled Dick’s enterprise.

Speer has made bullets and weights not available elsewhere—these .366 softpoints for the 9.3x26, for instance.

Vernon Speer’s firm became a leader in .22 rimfire ammo. It also makes the Gold Dot pistol line.

Not to be deterred, Dick looked to handloaders for another inspiration. He found that primers were a bottleneck on most loading benches. Major ammo firms couldn’t (or wouldn’t) ensure a steady supply of component primers. Dick Speer seized on this failing as an opportunity. In 1951 he hired explosives expert Dr. Victor Jasaitis from Lithuania to come up with percussive compounds to fuel a new business in primers for handloaders. His first products were FA-70 primers to fill government contracts. Later, Jasaitis came up with non-corrosive primers for sporting ammunition. To differentiate his business from Speer Bullets, Dick (with partner Arvid Nelson) changed his firm’s name to Cascade Cartridge, Inc. Now known universally as CCI, it soon outgrew its corner in Vernon Speer’s bullet plant. Dick bought a 17-acre chicken farm upriver, near the Lewiston Gun Club. In a converted coop under a tar-paper roof, he began producing rifle primers.

After the gun club moved, Dick bought that property, expanding his operation in 1957 to include manufacture of shotshell primers. Two years later he started making power loads—rimfire cartridges for nail guns and other industrial tools. Rimfire rifle cartridges were a natural sequel in 1963. CCI Mini-Mag ammunition soon became wildly popular. Four years after its debut, Dick Speer sold CCI to Omark.

The production of rimfire ammunition is highly specialized, and tooling up requires huge capital outlay. Consequently, there are few such factories in the US When Hornady decided to load its .17 HMR cartridge, it turned to CCI. Hornady’s tiny polymer-tipped bullets, combined with CCI’s manufacturing expertise and commitment to high quality, delivered to shooters accurate cartridges that became one of the greatest success stories of the industry in the last 40 years. By this time, CCI had improved its centerfire primers to give handloaders lower seating pressures and easier ignition. In 1991 it had opened a new primer plant in Lewiston and, subsequently, become a major supplier of cannon primers to the US armed forces.

Speer/CCI has become one of the most recognized brands in the shooting industry. Its bullets and primers and its handgun and rimfire ammunition are proven favorites. Now owned by ATK, which also counts Federal Cartridge, Weaver, and RCBS as assets, the enterprise Vernon Speer founded with Joyce Hornady continues to provide the best in ammo and loading components

Among the contemporaries of the Speer brothers was a hunting enthusiast who, in 1946 on a hunt in Canada, had to fire several shots to kill a moose. The bullets ruptured on the animal’s mud-caked hide and didn’t penetrate. “My .300 H&H was too powerful to kill a moose with the bullets of that day,” he told me, years later. He decided to build a better softpoint.

John Amos Nosler, 33, ran a trucking business in western Oregon. His father Byrd had been born on the Oregon Trail and raised on a homestead in Coquille. John arrived after Byrd had moved to Brawley, in southern California. The boy grew up on a ranch near Bishop, where his family raised horses and mules. During the Great War, Byrd sold mules to the government.

Turning a dollar here and there in real estate and hardware sales and delivering fresh milk, Byrd Nosler moved his family to Pomona, then to a ranch near Huntington Beach. “I was seven,” recalls John. “A year later, Dad took in an old Dort that needed service. I tinkered with it and got it started and sold it. What I wanted was a Model T. So I rode my bicycle around until I spotted one in permanent repose behind an old house. I went to the door and asked the lady there if she could use a bicycle. She eyed the derelict Model T and agreed to an even swap. I dragged that car home with Dad’s mules, fixed it up, and sold it.”

Automobiles became John’s passion. From Western Auto Supply he got parts for overhead-valve engines, and built them. “I came to believe that problems were really opportunities to improve on current designs.” John liked guns, too. He traded a set of Model T connecting rods for his first deer rifle, a .25-35 Winchester. But as the Depression tightened belts, the talented mechanic had to drop out of high school in his junior year. He went to work as clean-up boy at a Ford dealership in Chino for 15 cents an hour. That job led to more engine work, and racing. “A partner and I souped up a Model A with a B engine. I added counterweights to the B’s crank. It ran smoothly at 100 mph. Ford liked that crank well enough to adopt it.”

Known for bullets, Nosler now sells ammunition and even rifles. This Model 48 is in .338 Federal.

John married Louise Booz in 1933. Shortly thereafter he sold his new 1935 Ford and bought a ‘29 coupe for $60. The young couple moved to Reedsport, Oregon, where John managed a Ford dealership. In response to worker demands for unions, local sawmills soon shut down. Jobless people didn’t buy cars. To earn a living, John began trucking produce from California to southern Oregon. He bought one of the first Peterbilts ever made. It got only 6 miles to a gallon of diesel but could haul 20 tons—three times as much as a Ford. “Besides, diesel was 5 cents a gallon, gas 23.” By this time, John was shooting competitively and experimenting with handloads. He killed his first elk near Burns, Oregon.

Bob Nosler was born in 1946, as his father shifted from trucking for the war effort back to civilian markets. After the moose hunt, he also committed time to a new bullet. He made a hand press and bought a screw machine. He drilled out both ends of 5/16 copper billets turned to size, and pressed them into shape around lead cores. Fred Huntington of RCBS gave him new presses from his Oroville, California shop. The first Partition bullets weren’t accurate by current standards, but on their first hunt they put two moose down with two shoulder shots. John was on to something.

“That was more than sixty years ago,” Bob grins. Now CEO of Nosler, Inc., he runs the company with wife Joan (vice-president of corporate services), son John (vice-president and general manager) and daughter Jill (manager of corporate services)—“plus our hard-working employees. We’re very fortunate to have 125 dedicated people at Nosler.” The plant now comprises two buildings totaling 60,000 square feet in Bend, Oregon. “Big John,” 96, is still chairman of the board. “He drives a Lexus now,” grins Bob. “but he’ll talk to you about Model Ts and the Flying Mile at Long Beach.”

The family-owned company has expanded its product line considerably with Ballistic Tip bullets in 1984, following the Nosler Solid Base. “We were the second North American firm to employ a polymer bullet tip,” says Bob. “Canada’s Dominion brand had the Saber Tip first. But that company is defunct.” In contrast, many bullet and ammunition companies have adopted Nosler’s polymer design, which has earned an enviable reputation for accuracy and flat flight. It was followed in 2002 by the AccuBond, Nosler’s first bonded bullet. The lead-free E-Tip appeared in 2008. “Along the way we’ve also developed target bullets, handgun bullets, and brass solids for dangerous game. The Combined Technology bullets Winchester loads were designed mainly by Nosler.”

There’s also Custom brass with the Nosler head-stamp. “We weigh-sort it, chamfer case mouths, de-burr primer pockets and true necks,” says Bob. “It’s top-end brass, ready for the powder charge right from the box.” There’s also a Custom ammunition line, with offerings from .204 Ruger to .416 Weatherby. Nosler Trophy Grade ammo delivers all but the hand-finishing of Custom cases, at a lower price.

Nosler’s M48 in .338 Federal is a handsome rifle, potent enough for any North American game.

John Nosler developed the Partition bullet in 1947. Here he cradles a favorite M70, in .280.

Bob points out that Nosler gave legitimacy to one of my pet cartridges: the .280 Ackley Improved.

“We developed factory loads and shepherded the round through SAAMI’s approval process. It’s a fine big game cartridge—especially in Nosler rifles!” The company builds two. The Custom wears a walnut stock and Timney trigger. Its hand-lapped, match-grade barrel has “half-minute accuracy potential.” The 7-lb Nosler 48 features a Kevlar-laminated stock. CeraKote finish makes it just about impervious to rust. “We’ll guarantee ¾ inch three-shot groups,” says Bob.

Such high standards have distinguished Nosler products since John hand-turned the first Partitions.

One of America’s premier bullet companies, Hornady, has been responsible for some of the most celebrated bullet designs of late. Sixty years ago, Joyce Hornady concluded that only uniform bullets would give him the “ten shots in one hole” he sought. In 1949 he decided he could make a bullet as any he could buy. Other riflemen apparently agreed; his first year’s production brought $10,000 in sales.

The Grand Island, Nebraska company owes its beginnings to the partnership forged when Joyce Hornady and Vernon Speer fashioned bullet jackets from spent rimfire hulls. This idea not only helped them make varmint bullets cheaply; it kept them in business during metal shortages in the early 1940s. Joyce was quick to spot value in the specialized machinery and tooling dormant in government arsenals after the war. When he and Vernon Speer split up to seek their own fortunes, he bought as much as he could afford. The Hornady plant still employs Waterbury-Farrell transfer presses manufactured as early as the 1920s. Of course, they’re updated with computerized controls.

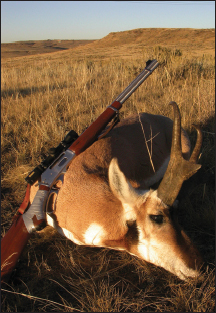

Wayne shot this pronghorn at 160 yards with a pointed FTX bullet from Hornady’s LeverEvolution .30-30 load. LeverEvolution ammo is a stunning success!

War in Korea interrupted Joyce’s budding bullet business. In 1958 he built an 8,000-square-foot factory that’s still company headquarters. Shortly thereafter, Hornady Bullets announced a new bullet nose design for flatter flight and better accuracy. The Secant Ogive softpoint has since distinguished Hornady’s hunting bullets. (Secant and tangent refer to the point from which an arc, measured in calibers, scribes the outline of the bullet nose. The tangent measure is taken perpendicular to the bullet axis at the cylinder/cone juncture. Secant measurements occur behind that point.) Tangent ogives have a more rounded form. Secant ogives minimize nose weight and air friction. While they don’t mandate a sharper junction between conical and cylindrical sections of a bullet, the secant ogive profile may appear more angular.

Hornady’s FTX bullet has given new life to lever rifles, now lethal at distance as well as in timber.

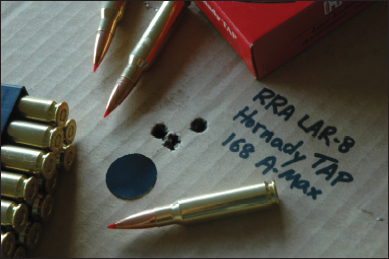

Hornady’s TAP ammunition delivers fine accuracy from Wayne’s LAR-8 from Rock River Arms.

In 1964 Joyce Hornady entered the ammunition business with his Frontier line. He used canister powders in once-fired brass, and his own bullets. Initial offerings: .243, .270, .308 and .30-06. The Viet Nam War choked off brass supplies. Joyce began buying new cases in 1972. At the same time, son Steve moved back from Lincoln, where he’d been working for Pacific Tool. He brought the company with him.

Hornady began as a bullet company. Now it also produces loaded ammunition and loading tools.

Joyce Hornady lost his life in a plane crash in 1981, en route to the SHOT Show in New Orleans.

“No one was prepared,” said Steve. “But our family was committed to growing the business. We were blessed with a talented crew.”

In 1983 Hornady Bullets, Frontier Ammunition and Pacific Tool Company were absorbed into a new Hornady Manufacturing Company. They retained autonomy as Hornady Bullets, Hornady Custom Ammunition and Hornady Reloading Tools. A year later, the enterprise was making its own cartridge cases in-house, and loading them. The firm would soon launch itself as a major player in the ammunition field.

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- CONTENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- SECTION I: BALLISTICS IN HISTORY

- SECTION II: THE MUSCLE BEHIND THE SHOT

- SECTION III: BULLETS—THE INSIDE STORY

- SECTION IV: SPEED, ENERGY, AND ARC

- SECTION V : PUTTING BALLISTICS TO WORK

- SECTION VI: FOR LONGER REACH

- BALLISTICS TABLES FOR MODERN SPORTING RIFLES

- GLOSSARY