26. Never a miss

Ask any rifleman why he shot a 9 instead of a 10, or missed an elk. He’ll expound on tricky winds or deceptive terrain or a hidden limb that caught his bullet—or a bad barrel or squirrely scope, an unproven load.

In truth, we miss because the bullet is pointed in the wrong direction when we launch it. There is no other way to miss. We can’t help but hit when the bullet heads in the right direction.

Long ago I was shooting a regional smallbore match in the Midwest. The competitor to my right was Johnny Moschkau, an unflappable old man who consistently shot tiny groups. The morning sun soon flooded the targets with heavy mirage. With a bit of luck I managed a ragged but still perfect 200 with my first 20 shots. Moschkau, I noticed, dropped a point. This made me feel very good indeed.

During the next stage of the 1600-point match, I kept one eye on Johnny’s target, the other on mirage. I shaded a few into the X-ring, listening for pauses in rifle fire on the windward end of the line to warn me of impending let-ups or reversals. Moschkau apparently wasn’t aware of all that. Still as a corpse on the mat, his left eye pressed to the spotting scope and his right in the sight-cup, he didn’t move except to finger the bolt up-back-down, up-back-down, with a mechanical drop of his hand to the loading block somewhere in the middle. Shooting fast. Then Johnny stopped.

Position, breathing, trigger control. Make sure the rifle’s natural point of aim is on target!

I looked at his target. Just 12 record shots. I kept firing. Johnny would run out of clock….

Suddenly the wind died, and my next bullet looped for a 9. My second. Heart thumping, I put three X’s in the sighter bull and lost two more points for score before finishing with a minute left. I swung my scope to Moschkau’s target: 16 holes. He lay like a beached crocodile, waiting for the condition he demanded. Then, with fewer than 25 seconds remaining, Moschkau’s rifle spat a bullet. X. The efficient bolt manipulation and loading resumed. The .22 cracked rhythmically. X. X. Ten seconds. Bang. Now five. Bang. Bang. X. X.

Among the most popular .22s ever, Ruger’s 10/22 is easily customized. It can be very accurate.

“Cease fire!” The range officer called it before Moschkau had ejected his last case. Johnny unlatched his sling, rolled over and asked how I’d weathered the bumps. Not too well, I said. He told me there were still lots of X’s left out there for people who aimed carefully and didn’t let a shot go until everything looked good.

I must report that Johnny Moschkau whipped me soundly at this event. His cool, focused attention to the target and to shooting fundamentals won out. My side-long glances at other targets broke my concentration. I knew how to shoot an X, but dividing my attention netted me sloppy 10s. And 9s. “Hitting is easier when you keep bullets on a tight rein,” Johnny grinned.

He was right, of course. Executing shots carefully helps you hit. But that’s not all there is to know.

After you’ve established your zero, you must trust it, putting the intersection of the crosswire right where you want to hit. One of the most common failings of hunters is thinking when they should be shooting. The reticle should stick where you want the bullet to strike. Compensation for range and wind is not necessary as often as most hunters think it is. They typically overestimate range. Wind has little appreciable effect on hunting bullets at the ranges most game is killed.

Tom Gallagher bolts in another round during practice. Follow-up shots should be automatic.

Another hunter and I once trailed a herd of elk along the side of a deep coulee. Just at dusk, we peeked over a rise and spied them 150 yards off. The hunter fired, dropping a bull. But the animal got up and staggered away. The man shot his rifle dry, then reloaded. None of the bullets hit. Meanwhile, the elk went down again. We ran forward and finished it up close. The bull’s front legs had been shattered by the first shot; this fellow later admitted he had aimed low every time. Why? He couldn’t say.

I’ve had a great deal of experience aiming where I shouldn’t. Once I drew a bead on an elk that gave me one shot at about 280 yards. My 160-grain handloaded bullet would land about 4 inches low, I figured— no need for holdover. Perversely, I aimed at the spine. The elk died quickly, but the hit was most certainly high. Another time, I surprised a group of elk on their way to bed. The animals were walking fast, but at 60 yards a dead-on hold made sense. Maybe I confused the speed of my pulse with that of the elk—anyway, my bullet whizzed in front of the bull’s chest. I got a second chance after tracking this animal, and made the most of it.

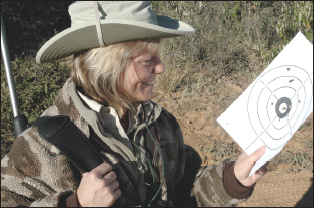

Weather shouldn’t affect your focus. This hunter cycles her Blaser smoothly, from long practice.

In pronghorn country, shots can be long. Ballistic superiority won’t trump a steady position.

Another bull was not so generous. When my Nosler clipped a wad of hair from his brisket, he throttled up. Dutifully I took the trail. It was easy to follow, but as bloodless as cabbage.

My willingness to aim anywhere but where I want to hit may derive from my youth, when BBs cost a nickel a pack and I amused myself attempting impossibly long shots with an air gun. The lazy coppery arc of a BB is more like that of an arrow than a bullet. Beyond 20 feet, I had to elevate. The fickle ball sidestepped at the mere suggestion of a breeze. Aiming at the mark was the surest way to miss it.

Aperture sights can deliver fine accuracy—as far as you can clearly see the target.

Later, shooting rimfire rifles in competition at 50 feet, I had no worries about gravity or wind. But my pulse and quivering muscles wouldn’t allow the sights to settle. A slow trigger squeeze was OK for shooting from a bench or solid position, but offhand the only way I could nip an occasional 10 was to grab the last ounce as the muzzle strafed center. This technique was known by those of us who adopted it as a controlled jerk. Like any other jerk, it moved the rifle; so we had to correct not only for rifle movement before the jerk, but for the barrel’s leap or dip when our adolescent fingers bumped the striker into free-fall.

Shooting sticks get you above tall grass and make offhand shooting almost as steady as sitting.

While I still shoot poorly offhand, my bullets don’t stray quite as far as they used to. That’s because I learned, after many misses, to trust my rifle and hold it still.

Trust is more than using a center hold within point-blank range. It means you jettison every excuse having to do with rifle, sight and ammunition. If your equipment isn’t good enough, buy better. In competitive circles, amateurs remain so until they get rifles that shoot tight enough to win every match. They can then forget about equipment and build their skills to that standard. On the other hand, hunting rifles needn’t shoot as well or cost nearly as much as target rifles. A big game rifle that shoots into an inch and a half at 100 yards should earn your confidence. A rifle that manages no better than 2 minutes of angle won’t cause you to miss. At some point, you’ll have to accept your gear as adequate and hold yourself accountable for each shot. Practice, not excuses, makes you confident and competent. How would you like to board a 747 behind a pilot who, as he settled into the cockpit, told passengers the flight would be smoother, safer and faster if he had a good airplane?

Left-handed, this moose guide favors a Browning autoloader. He makes good use of field rests.

Before hunting make sure all handloads feed smoothly—down and up. Practice with a full box.

Some rifles are choosy about ammunition. If you have a rifle that doesn’t like any brand you feed it, sell it. You didn’t marry it. The same goes for scopes. While you can wager your mother-in-law’s good graces on the reliability of modern scopes, the one you bought must satisfy you. If it doesn’t, get rid of it. You must have confidence in your hardware. If top-flight marks-manship is your goal, you’ll do well to get beyond the equipment hurdle right away, so you can invest your time learning to steady a rifle and control its trigger.

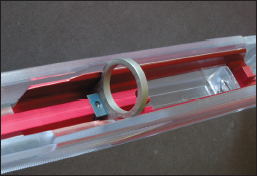

Savage engineers developed AccuStock, with a molded-in alloy rib and action frame, and a wedge that pulls the recoil lug tight in its seal. More consistent bedding means more accurate shooting.

Holding a rifle still without a rest is so hard that hunters commonly refuse to try it in public, shooting only from the bench. But your body won’t train itself as a shooting platform until you deprive it of that bench.

You can save money by dry-firing in your living room at a thumbtack on the wall. Dry-firing won’t hurt most centerfire rifles. It enables you to practice much more often. An understudy rifle can help with live fire. The J. Stevens Arms & Tool Company developed, in 1887, the .22 long rifle cartridge, and it’s been the best training aid for shooters ever since! Match-quality .22 rifles and ammunition are expensive, but they’re not necessary for practice. Taping tire weights to a cheap.22 can give it the balance of your hunting rifle.

I once watched a hunter miss an elk about 160 yards distant. His rifle was resting across a spotting scope on a tripod. The bull stood obligingly, waiting. When dirt flew from the hillside, both elk and hunter showed some surprise. In the firestorm that ensued the elk expired and the hunter said he couldn’t fathom how he missed a target the size of a California beach towel. I fathomed it because I’d been a dispassionate observer. The fellow had laid his rifle across the scope without padding it with his hand. He shook. He fired too quickly. He yanked the trigger. “Some shots just can’t be figured out,” I said generously.

Tight groups from a rest may not be as valuable as a target reflecting practice from field positions.

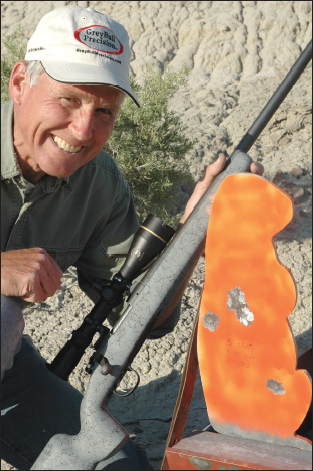

Practice! Wayne peppered this steel rodent prone from 500 yards, with a Remington 700, .22-250.

A logical sequence to the Icon sporting rifle, the heavier T/C Tactical rifle has an adjustable stock.

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- CONTENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- SECTION I: BALLISTICS IN HISTORY

- SECTION II: THE MUSCLE BEHIND THE SHOT

- SECTION III: BULLETS—THE INSIDE STORY

- SECTION IV: SPEED, ENERGY, AND ARC

- SECTION V : PUTTING BALLISTICS TO WORK

- SECTION VI: FOR LONGER REACH

- BALLISTICS TABLES FOR MODERN SPORTING RIFLES

- GLOSSARY