16. The All-Copper Option

For centuries lead has remained unchallenged as bullet material, but lately the all-copper bullet has grabbed headlines. In 1981, after traditional soft-nose bullets failed to pass muster on a hunting trip, Randy Brooks hatched the idea of an expanding bullet with no lead core. Others had toyed with the idea; but no one had brought a viable product to market. Randy and wife Coni then owned Barnes Bullets. While he continued manufacturing Barnes Originals, Randy shifted the firm’s focus to solid-copper hollowpoints. Soon the Barnes X became as well-known among hunters as Nosler’s famous Partition, the dual-core big game bullet dating to 1947.

The X-Bullet drove deep, though its petals did not open as broadly as those on traditional lead-core bullets. Coated X-Bullets followed, the blue film reducing bore friction and copper fouling—both liabilities endemic to solid-copper bullets. Then came Barnes Triple Shock (TSX) bullets, with four circumferential grooves to reduce bearing surface and give shank material a place to move under land pressure. The Triple Shock soon became known for its deadly terminal performance, and for more consistent accuracy than the X-Bullet. The recent addition of a polymer tip gave the TSX a higher ballistic coefficient. Now this bullet has a rival: Barnes’s own MRX. Its nose section is all copper, a hollowpoint with a polymer tip. It has the TSX profile with shank grooves. But inside the copper envelope of the shank, you’ll find what Barnes calls a “tungsten-based Silvex” core. Extending from just behind the ogive to the heel, it adds heft without lead.

A Browning X-Bolt in .308 drilled this half-minute group with 150-grain TSX bullets.

Now other bullet makers have introduced hunting bullets of copper or gilding metal construction, arguably in response to a lead-bullet ban in southern California condor range. Winchester and Remington, Nosler and Hornady plan to increase their lead-free bullet offerings. Ammunition firms will surely add to their lead-free loads. There is even a lead-free .22 WMR round from CCI (TNT Green). Are jacketed lead bullets on their way out? How do copper bullets compare ballistically with lead-core bullets?

First, a clarification: “Solid copper” is commonly used to describe these bullets. They are not solid in the sense that non-expanding bullets are solids. They’re designed to mushroom. A hollow cavity ruptures the nose, enabling pre-scored petals to peel back, increasing diameter and destruction. Here “solid” refers to the bullet’s composition: either solid (“pure”) copper or gilding metal—copper/zinc alloy.

“Give up lead, and you give up speed in certain cartridges,” says Hornady’s chief engineer Dave Emary. “Cases designed for full-capacity charges behind heavy bullets don’t do quite as well with copper or gilding metal bullets, because to make weight, so to speak, these bullets must be longer than lead-core bullets. You have to put that extra length somewhere. Seating a bullet deeper reduces case capacity. Seating it to greater overall length can cause interference in the magazine or throat. Any copper bullet with the dimensions of a lead-core bullet will be lighter. It will not retain its velocity as well or carry quite as much energy.” Yes, you can start light bullets faster. “But a little more speed at the muzzle won’t offset a higher ballistic coefficient downrange,” says Dave. “And because copper is harder than lead, and gilding metal harder still, you can’t accelerate a lightweight non-lead bullet quite as fast as a traditional softpoint without boosting pressure. There’s too much bore friction from that hard shank.”

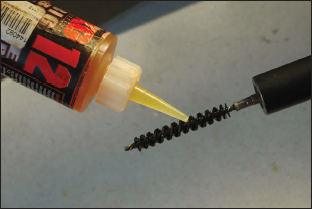

Bore-cleaner on a brush removes metal fouling, a bigger problem with solid-copper bullets.

A sabot sleeve falls away after exit endows shotgun slugs with the ballistic properties of rifle bullets. They have smaller diameters, sleeker profiles, higher sectional densities than traditional, bore-diamter Foster slugs. Note the huge nose cavity, to ensure upset at relatively low impact speeds.

Another concern that attends copper and gilding metal bullets is throat life. Most hunters needn’t worry. While harder bullet material hikes friction and accelerates wear, few sportsmen shoot enough to ruin a throat with these bullets. And competitive shooters have so far stayed true to lead-core bullets.

Dave tells me that solid copper hunting bullets incorporate compromises in the nose. “You want an aerodynamic ogive, a pointed profile. But the small nose cavity in bullets of this shape doesn’t initiate upset at low impact speeds. We can make the cavity bigger—but only at the expense of ballistic coefficient. An open nose also tends to shatter when driven fast into tough targets. Copper bullets expand satisfactorily in a relatively narrow velocity window. We can make lead-core bullets that penetrate well when striking an elk at 3,000 fps but still open reliably in deer at speeds as low as 1,600. It’s difficult to make a copper bullet expand at less than 2,000 fps unless you make the cavity so big the front end disintegrates at 3,000.” Small-diameter bullets—25-caliber and under—pose a challenge in nose design because there’s so little material forward of the shank. A slender nose limits options for cavity diameter.

As for penetration, the copper bullet does just fine, typically retaining more of its original weight than lead bullets and delivering a more symmetrical blossom, which tends to drive straighter. On average, petals on copper rifle bullets don’t gape quite as widely as jackets on lead bullets, assisted by the smashed core. But while double-diameter upset of a fast lead bullet opens a huge cavity in the vitals, damage caused by a copper bullet 1 ½ times its original diameter can be stunning, and penetration deeper. Not long ago I shot a couple of Australian buffalo with Barnes .338 TSX bullets. Both drove to the off-side. One hit the massive knuckle of the off-shoulder so hard it shattered the wrist-thick bone at mid-section, inches from point of impact. I couldn’t imagine any lead-core bullet dealing a more destructive blow.

The TSX bullet from Wayne’s iron-sighted Savage in .338 penetrated to the off-side shoulder knuckle of this Australian buffalo. The impact shattered the massive bone well below the joint.

Accuracy, too, can be on par with that of jacketed bullets. I’ve drilled tight groups with TSXs, and Dave Emary tells me the lead-free GMX bullet is as accurate as any of Hornady’s lead-core hunting bullets. “GMX” stands for “gilding metal expanding.” Designing it in 2009, Hornady chose gilding metal (5 percent zinc) over pure copper because it’s less prone to fouling. It’s also more brittle. Preventing breakage during upset proved a challenge. Hornady met it. Like the Barnes TSX, the GMX has circumferential grooves or driving bands. “We settled on two of standard .045 cannelure width,” says Dave. “They proved significantly better than one; with three we gained no perceptible advantage. The grooves reduce full-diameter shank surface by about 20 percent and give the shank material room to move under land pressure.”

“The gilding metal is the same material we’ve used for years in Hornady bullet jackets,” explains Jeremy Millard, who headed the GMX project. He tells me the GMX bullet expands and penetrates reliably at impact velocities of just under 2,000 fps to 3,400 fps. “Typically, we get 99 percent weight retention in ballistic gelatin. All we lose is the tip.” The GMX’s scarlet plastic tip is just like that on the Hornady SST. In fact, the two bullets look the same when loaded. In flight, the GMX acts like the SST. “We designed the bullet to duplicate the SST’s arc when driven at the same speed,” Jeremy says. “The ballistic coefficient is almost identical. You can use SST load data.”

But inside, these two bullets differ. Besides lacking the SST’s lead core, the GMX has a unique cavity. “The front end is parallel-sided to accept the tip,” says Jeremy. “As on the SST, that’s roughly a 3/32 inch channel. But the GMX cavity tapers to a nearly a point even with the base of the ogive. That’s where we want expansion to stop. And that’s where it does.”

GMX bullets are cut from wire, swaged to shape. Jeremy emphasizes that dimensional tolerances are very tight. “We demand that these bullets not only deliver the upset hunters want, but that they shoot accurately.” He concedes that they cost more than lead bullets. Though the price of lead has risen, it’s still a fraction of the cost of copper, which has climbed to record levels over the last few years. “On average the GMX retails for about 40 percent more than our Interbond bullets,” he says.

Shortly after a pre-production sample of 30-caliber GMX bullets became available, I hurried off to British Columbia to hunt moose with my friends and outfitters Lynn and Darrell Collins. We’d traveled southwest from their Quesnel base to the remote mountains below the Bella Coola Highway. Though local bulls had not yet felt the heat of rut, we eventually found one on a timbered hill. Shooting prone through a tight alley in the brush, I threaded a 150-grain GMX 105 yards to the shoulder. The moose fell backward and did not move. The bullet, from my Ruger Hawkeye in .300 RCM, had sailed through the near scapula into the spine. It had apparently stopped there; no exit wound was evident in the off-shoulder. Eviscerating the bull, I found considerable lung damage, from bone or bullet fragments or both. The massive chunk of bone comprising moose spine between its shoulders is, of course, a very tough assignment for any bullet.

Neil Jacobson shot this outstanding gemsbok with a lead-free Winchester E-Tip bullet from his Remington .30-06.

Nosler knows about the challenges of making effective copper bullets. Its E-Tip bullet showed up first in Winchester ammunition. Now Nosler hawks 150-and 180-grain .30-caliber E-Tips as components. “This bullet is all gilding metal,” explains Bob Nosler, “95 percent copper, 5 percent zinc. We call it 210 alloy. It has great tensile strength. E-Tips don’t foul barrels as readily as copper bullets. A deep expansion cavity ensures upset in light game.” That cavity is capped by a polymer tip for a high ballistic coefficient. It helps trigger expansion. The Nosler/Winchester E-Tip bullet features a tapered heel, or boat-tail. There are no circumferential grooves. E-Tips loaded by Winchester have the firm’s familiar black Lubalox coating.

The E-Tip owes much to Glen Weeks, Winchester’s centerfire ammo guru, who collaborated with the Nosler crew to deliver this bullet at record pace. Work began in October, 2006, and prototype bullets appeared at the April, 2007 NRA convention. “E-Tip’s metal is as hard as or slightly harder than copper,” says Glen, “so it has less tendency to gall. That means easier bore cleaning and reduced metal fouling.” I took E-Tip bullets to Africa recently and found that even on big, tough antelope they penetrated very deep.

Small but lethal at 3,800 fps: Winchester’s .223 with 35-grain Ballistic Silvertip lead-free bullet.

A burly gemsbok bull dropped to one E-Tip from a .30-06. The spitzer passed through. An unnecessary follow-up shot gave me a recovered bullet, slightly deformed after shattering the shoulder, but very nearly as heavy as when it left the bore.

What about sealing in the bore? To cork powder gas and ensure an authoritative bite by the rifling, bullets must be malleable. Lead-core bullets “slug up” nicely to fill the grooves. Not so copper and gilding metal. I asked Glen about the bullet’s accuracy and the pressure issue some companies have addressed with shank grooves.

“The secret to E-Tip’s fine accuracy is its deep nose cavity,” Glen says. “It extends well below the tip, down even below the ogive. So the leading portion of the shank can yield slightly as the rifling begins to engrave. Gas pressure on the bullet base clinches the deal, ensuring that E-Tip is securely gripped and seals the bore.” The cavity also moves center of gravity back toward E-Tip’s tapered heel. Better accuracy results. As for terminal performance, E-Tip delivers four-petal upset. But unlike solid-copper bullets, E-Tip winds up with a broad face, resembling that of a traditional softpoint. “It won’t drive quite as deep as the AccuBond,” adds Glen. “It behaves more like the XP3.” That’s Winchester’s most recent lead-core bullet—one hailed for its versatility. The company loads 180-grain E-Tips to standard lead-bullet velocities.

Remington has a lead-free big game bullet, in a Premier Copper Solid line of hunting ammunition. The polymer-tipped spitzers have two shank grooves and tapered heels and are listed as solid copper. “They were designed to expand reliably over a wide range of velocities,” explains Linda Powell, the company’s press contact and a dedicated hunter who knows as much about Remington ammo as anyone. “Our goal was double-diameter upset with 98-percent weight retention in tough game. We’re on target.” Remington’s lead-free ammo includes .223 and .22-250 Disintegrator loads with 45-grain bullets at 3,550 and 4,000 fps.

Frangible lead-free varmint bullets shatter the popular illusion that lead is necessary if you want explosive upset. Barnes serves prairie dog shooters with its Varmint Grenade, a flat-base hollowpoint bullet with a copper-tin core and gilding metal jacket. Like the Barnes MPG (multi-purpose green) bullet in 5.56 and 7.62mm, the Grenade ruptures immediately and violently. Randy Brooks is pleased with the reputation his X-Bullet and TSX have earned for deep penetration and high weight retention in tough game. But he’s quick to praise his varmint bullets—and to point out that solid-copper bullets for deer-size animals deliver the accuracy and broad wound channels hunters have come to expect of lead-core softpoints. “Our hunting bullets aren’t just for Volkswagen-size moose and bears. They’re versatile. Match the bullet to the game, and you’ll find them ideal for pronghorns and white-tails as well as for heavy animals with thick hides and big bones.” He adds that solid-copper Expander MX hollowpoint muzzleloading bullets have performed superbly in deer-size game at modest impact speeds.

What about other non-lead materials? Tungsten is denser than lead and performs successfully in shotshells. But it’s frightfully expensive—several times the price of lead. “We considered tungsten for Dangerous Game solids,” Dave Emary tells me. “But our jacketed lead-core bullets work as well and cost less.” Those solids wear a laminated jacket, copper sandwiching steel. “So we get the strength of steel with the surface properties of copper.” A solid bullet for elephants could, of course, be constructed of copper or gilding metal. But sectional density matters a great deal when the bullet must drive through massive bones.

Winchester ballistician Glen Weeks covers gelatin with cloth in tests of bullet upset, penetration.

Of major US bullet companies, only Sierra and Swift have yet to list a lead-free centerfire bullet.

Carroll Pilant, shooter and long-time press liaison at Sierra, says tests of lead-free bullets have not shown them to be viable substitutes for lead. “Copper bullets won’t deliver the accuracy we get with MatchKings. We’d be foolish to replace an iconic bullet like the MatchKing—the choice of an overwhelming majority of competitive shooters.” Pilant hasn’t heard of anyone at a high-power match choosing lead-free bullets. Nor does he think copper bullets equal Sierra’s GameKing for either accuracy or devastation in deer-size game.

While Winchester and Remington have introduced their own lead-free bullets, Federal has not. Its preference: Offer bullets from the nation’s top bulletsmiths. Jason Nash at Federal emphasizes that the firm has traditionally given hunters many options. “We’ll continue that policy, with bullets from our house and specialty lines like Nosler, Barnes, Sierra and Woodleigh.” Federal’s Trophy Bonded Bear Claw has a big following among elk hunters. The company is currently pursuing a viable lead-free .22 Long Rifle round.

As lead-free bullets gain traction at market, they’ll get more attention from engineers charged with improving them. During development of Hornady’s GMX Dave Emary was keen to add Flex Tip polymer noses for use in rifles with tube magazines. It proved a tough assignment. “Lead-core bullets obligingly grip an FTX peg. A gilding metal nose isn’t as malleable.”

Does the addition of a soft or hard polymer nose affect the terminal performance of a gilding metal bullet? “A hard polymer tip makes upset more violent,” Dave replies, “especially at high impact speeds. An FTX tip does not—but it helps trigger expansion at low velocities.”

Pointed noses and long ogives help bullets cleave air. But the form factor is just one component of ballistic coefficient, which includes sectional density. Reducing weight reduces sectional density, so a lead bullet has a slightly higher ballistic coefficient than an all-copper bullet, given the same nose profiles. The shank of a lead bullet is shorter, so there’s less skin friction. But the disparity is small. A 165-grain 30-bore jacketed bullet with a ballistic coefficient of .450 beats its copper or gilding metal rivals by only .015 or so. Currently, lead-free bullets cost more than traditional jacketed bullets. That could change as more makers develop more bullets of copper and gilding metal. The industry has made this commitment—though only Remington calls its bullets non-toxic. Other companies share my view that non-toxic is an unfortunate moniker. It implies that lead-core bullets are toxic.

Even outside the shooting industry, the toxicity of lead has become a headline topic of late. Most worrisome to shooters is the recent lead ban in California to prevent condors from eating bullet fragments while scavenging animals killed by hunters. The science behind this decision has been questioned. Despite warnings in the general press about lead fragments posing a threat to people who eat venison taken with softpoints, there’s no substantiating evidence. After a politically motivated decision to pull tons of donated venison from food programs for the needy in North Dakota, the state has recanted. A report issued by the Epidemic Intelligence Service of the National Center of Environmental Health detailed a study of lead levels in 734 North Dakotans, 80 percent of whom claimed they ate venison year round. Blood tests showed mean lead levels of less than 1.5 ng/dl, with only 8 of participants (1.1 percent) testing over 5 ng/dl. The highest individual reading, an outlier, was still well below the 10 ng/dl considered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to warrant case management. A response by the National Shooting Sports Foundation noted that lead levels in workers exposed to lead would have to reach 60 ng/dl before OSHA would require employees to be furloughed. The difference in blood levels between people who ate venison and those who did not? Just .3 ng/dl. No wonder most companies making non-lead bullets hesitate to call them non-toxic!

Lead bullets remain the most popular bullets. The best of bullets made without lead simply give hunters more choice.

Choice is good. Which is why state efforts to limit bullet choice are not.

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- CONTENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- SECTION I: BALLISTICS IN HISTORY

- SECTION II: THE MUSCLE BEHIND THE SHOT

- SECTION III: BULLETS—THE INSIDE STORY

- SECTION IV: SPEED, ENERGY, AND ARC

- SECTION V : PUTTING BALLISTICS TO WORK

- SECTION VI: FOR LONGER REACH

- BALLISTICS TABLES FOR MODERN SPORTING RIFLES

- GLOSSARY