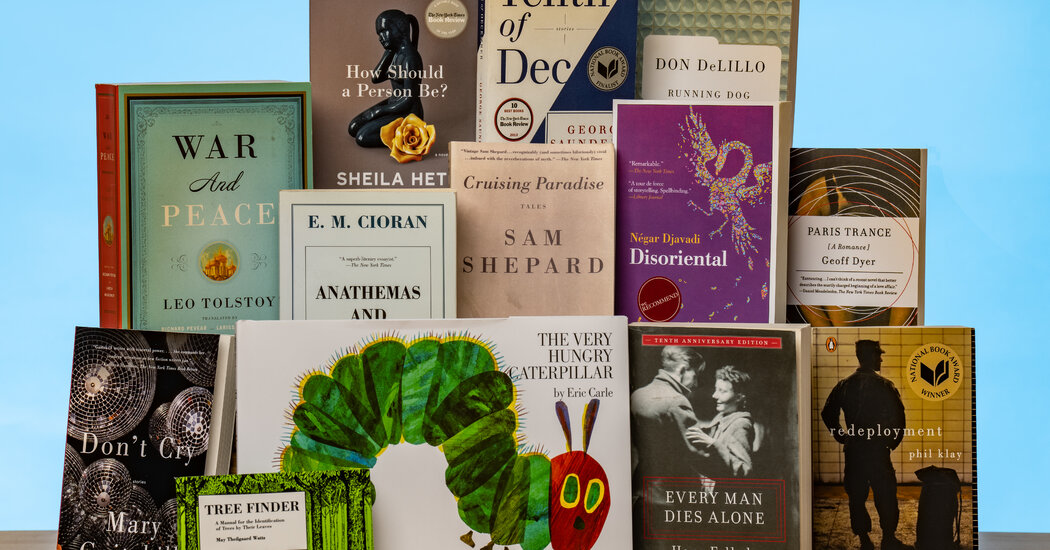

It appears on book covers by everyone from Jane Austen to William Faulkner to Martin Amis, but naming specific examples is a silly exercise. Walk into any bookshop and you’ll find that a good number of book covers feature Bodoni, a typeface created by Giambattista Bodoni in the late 18th century.

Few other type families have proved so relentlessly useful over the centuries. If you read books, a piece of Bodoni is probably lurking on your shelf in gorgeous silence right now. Brand logos that either are Bodoni or owe a serious debt to it include Valentino, La Mer, Calvin Klein and Brookstone. The typeface appears on album covers from Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the U.S.A.” to Lady Gaga’s “The Fame.”

With its straight hairline serifs and high degree of contrast between thick and thin strokes, Bodoni has an elegant literary appearance. It has inspired countless riffs and copies. A graphic designer seeking shorthand for “sophisticated” might reach for Bodoni or one of its relatives.

The typeface was also one of six preferred by the legendary graphic designer Massimo Vignelli, most famous for designing the visual system of the New York City subway in the 1970s.

The Museo Bodoniano in Parma, Italy, offers a glimpse inside the mind of the immortal typographer. At its entrance stands a bust of Bodoni. It is a bust in two senses of the word. One, it is a sculpted likeness of a renowned figure. Two, it depicts its formidable subject topless and flashing a nipple.

Bodoni was born in 1740 in the town of Saluzzo to a family of printmakers. As a teenager he served an apprenticeship at the Propaganda Fide printing house in Rome, where he learned the sweaty skills of setting metal type. He then struck out on his own and wound up in Parma, where he lived and worked until his death in 1813.

A few steps into the museum stands a reproduction of Bodoni’s printing press. The contraption of cranks, planks and straps resembles an antique Pilates reformer machine built on the scale of an ogre. It implies the hard labor involved in typecasting: the stamping, hammering and punching; the handling of molten metal and the proximity of blasting furnaces.

Along with brute strength, the craft required fearsome tools. Vitrines at the museum feature Bodoni’s anvils, hooks, blades, clamps, awls, calipers, files and pliers. These instruments of glinting steel bring to mind the lair of a cinematic serial killer. Happily, they were used for the higher purpose of creating standardized, aesthetically pleasing and instantly legible characters. (That said, one trait Bodoni could be said to share with movie serial killers was, per a placard, “una maniacale attenzione per ogni fase del lavoro,” or “a maniacal attention to detail.”)

By middle age Bodoni achieved the kind of celebrity we now associate with pop stars and presidents. Aristocrats sang his praises. He hung out with the pope. Benjamin Franklin developed a long-distance obsession with one of his printing manuals. Napoleon was a fan.

The museum — which is really more of a gallery, measuring only 50 paces in length — ends with a compact selection of Bodoni’s works. On display is the first book printed in Parma by Bodoni; it is a collection of poetry from 1768. There is an edition of Dante’s “Divine Comedy” from 1796. There are works on translucent parchment and veined ivory silk. There is an 1809 manuscript that, as a placard points out with unconcealed indignation, took 15 years to complete “due to countless problems caused by the confiscation of art objects the French pursued.” Thanks to this vexing interference from the French, the work was unfinished when Bodoni died. His widow, Margherita Dall’Aglio, completed the job.

The Bodoniano Museo sits within the larger complex of the Palazzo della Pilotta, a 16th-century palace that now houses cultural institutions like the Teatro Farnese, the Galleria Nazionale and the Museo Archeologico.

After canvassing the Bodoniano there was time to perch in the Palazzo’s grassy piazza and enjoy a spell of Saturday evening people-watching. Despite a chilly temperature of 32 degrees, the grounds teemed with beer-sipping locals, vaping zoomers and the odd nun. (The dominant beer brands appeared to be Heineken and Beck’s. Perché?)

Fashion trends on display included winged eyeliner for the ladies and hair dyed in one of two schemes: inky black or a snow-cone swirl of ash and platinum blond. Fur coats in eggplant or chestnut were paired with knee-high boots. Older men favored leather jackets with pointy, 1970s-style lapels. (You heard it here first: Lapels broad enough to be visible from behind are back.) For teens the most popular color palette was head-to-toe black with chic fluorescent-pink accents. Young men wore flat caps of the kind donned by Brad Pitt in 2010 — or, for that matter, by their more senior Italian countrymen for centuries.